Join us for conversations that inspire, recognize, and encourage innovation and best practices in the education profession.

Available on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, Google Podcasts, and more.

Things Fall Apart is a very famous book, and one of the few books by a contemporary African writer that is widely assigned in U.S. high schools. For good reason: Things Fall Apart is the short, swift story of one man’s rise and fall as world events play out around him. It grabs your attention from the first page and leaves you thinking about what you’ve read long after you’ve finished.

Chinua Achebe’s story gives us a picture of the Igbo people (who live in what is now Nigeria) at the turn of the twentieth century. The Igbo, or Ibo (pronounced “EE-bo”) see their complex and sophisticated society challenged by the British, who first appear in the village in the form of Christian missionaries and then as colonial rulers. The increasing friction leads one man to make the ultimate rejection of European ways, while the rest of his neighbors, family, and friends try to understand what the future holds.

“One of the things that Achebe has always said, is that part of what he thought the task of the novel was, was to create a usuable past. Trying to give people a richly textured picture of what happened, not a sort of monotone bad Europeans, noble Africans, but a complicated picture.”

CE

1600s

Western Igbo kingdoms dominate trade in the lower Niger region.

1815

Following the end of the Napoleonic wars between France and Great Britain, Britain begins to trade with the interior, calling the region “Nigeria” based on the path the Niger River takes through the area.

1914

Igbo, Yoruba, and Hausa areas are officially united under Britain as the Colony and Protectorate of Nigeria.

1930

Chinua Achebe is born in the Igbo village of Ogidi.

1958

Things Fall Apart is published in England.

1960

Nigeria gains independence, as a parliamentary democracy.

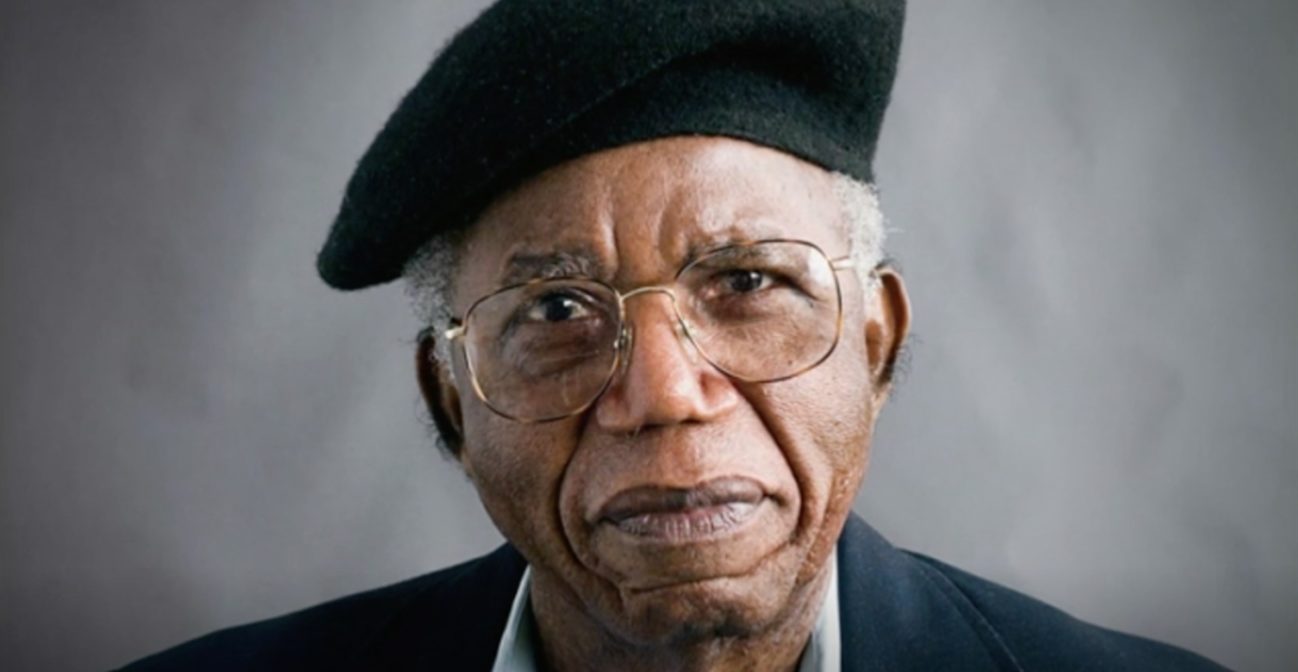

This story of the Igbos around 1900 was written by one of their grandchildren; Chinua Achebe was born in 1930 in southeastern Nigeria, in the Igbo village of Ogidi. He grew up speaking English and reading English literature, but Achebe kept a deep attachment to his Igbo roots; eventually he came to question the English literary portrayal of Africa and Africans as violent, ignorant, and primitive. Achebe wanted to give Africans their own voice, to take control of how they were seen, and to repair their own self-image.

The result was Things Fall Apart. The hero of the story is Okonkwo, a self-made man who has been unstoppable in his determination to rise in his society, the village of Umuofia. His greatest fear is being weak, like his father, whom he detested. Okonkwo will go to any lengths to prove to the world and to himself that he is strong and fearless—even to the point of destroying himself.

Umuofia is not a paradise or a hell. Its people are not evil and ignorant, nor are they innocent, noble savages. These European points of view are discarded. Umuofia is filled with real people who have complex personalities. When the British missionaries arrive in Umuofia, it is shocking to realize that most of them would destroy Igbo culture without a second thought.

But Achebe’s refusal to paint the conflict in black and white is what makes Things Fall Apart so powerful. Just as Umuofia was not perfect, the British are not all evil. The missionaries offer acceptance, love, and respect to those Igbos who have been outcast by their village for religious reasons. If only the two groups could have met in a spirit of compromise, they might have been able to live peacefully together. But the British insistence on domination, and the Igbo fear and rejection of their people who convert to Christianity, spell doom for Umuofia. Each side fears the other, and, like Okonkwo, each side is so fearful of appearing weak that it will resort to violence to keep the upper hand. Achebe shows that the coming of Europeans to Africa was not light coming to darkness, or pure evil destroying a people; it was two imperfect societies set on a collision course from which neither could emerge whole again.

Achebe wrote Things Fall Apart in English. The decision was controversial amongst African writers at the time, some of whom wanted to promote native African languages, while others accepted English. If Achebe wrote in English, he was using the language of the colonizer, a non-African voice, to tell an African story, once again. But if he wrote in Igbo, he was limiting the potential audience for the novel to a single group of people in Nigeria.

In an essay called “The African Writer and the English Language,” Achebe describes the problem:

For an African writing in English is not without its serious setbacks. He often finds himself describing situations or modes of thought which have no direct equivalent in the English way of life. Caught in that situation he can do one of two things. He can try and contain what he wants to say within the limits of conventional English or he can try to push back those limits to accommodate his ideas… I submit that those who can do the work of extending the frontiers of English so as to accommodate African thought-patterns must do it through their mastery of English and not out of innocence.

In other words, African writers can use English to change it, and turn it into a language of African experience and not just English experience.

Achebe changed English by infusing it with Igbo syntax, usage, and vocabulary so that while Things Fall Apart is clearly written in English, it is a new kind of English that serves an Igbo purpose.

Mr. Brown

The first white missionary to arrive in Umuofia, Mr. Brown is respectful and patient, never attacking clan customs or religion directly. His early success is endangered by his ill health.

The District Commissioner

The highest English official in the region arrives with the missionaries and oversees the fall of the villages from a distance.

Ekwefi

Okonkwo’s second wife, who left her first husband for Okonkwo. She has borne ten children and lost all but one, her daughter Ezinma. Her love for Ezinma leads her to stand up to Okonkwo on occasion.

Ezinma

She is Okonkwo’s favorite child, beautiful and connected to her father in a deep way. Only she can understand him and his moods. Her only flaw, in his eyes, is being a girl.

Ikemefuna

A boy from a neighboring clan who is seized by Umuofia warriors. He lives with Okonkwo’s family as a peace offering, and is a more satisfying son to Okonkwo than Nwoye.

Okonkwo

This self-made man has worked his way up from poverty and, as he sees it, freed himself from the disgrace of having a lazy, “feminine” father. While Okonkwo possesses real virtues of hard work, far-sightedness, devotion to his clan, and love, these co-exist uneasily with impulses of fear, pride, and impatience.

Nwoye

Okonkwo’s eldest son shows every sign―so far as Okonkwo is concerned―of being a lazy, weak man like Unoka. Beaten and belittled by his father, Nwoye will become a prime target for conversion by the English missionaries.

Nwoye’s mother

Okonkwo’s first wife, whose name is not told to the reader. She, unlike her husband, understands the value of pity, gentleness, and forgiveness. Her stories instruct and delight the children.

Obierka

A thoughtful member of the clan who is Okonkwo’s best friend. He tries to help Okonkwo navigate the troubles that come to him, and is left cleaning up after Okonkwo’s catastrophic end.

Ogbuefi Ezeudu

The highest-ranking man in the village, and holder of three titles―a great rarity.

Mr. Smith

The far more zealous Smith replaces Brown and leads his new converts on a full-scale war of ideas against the village.

Unoka

Okonkwo’s father, a gentle musician who left his family poor and in debt at his death. He held no titles of rank in the village―driving Okonkwo to vow that he would hold many.

Editions

Mr. Brown

The first white missionary to arrive in Umuofia, Mr. Brown is respectful and patient, never attacking clan customs or religion directly. His early success is endangered by his ill health.

The District Commissioner

The highest English official in the region arrives with the missionaries and oversees the fall of the villages from a distance.

Ekwefi

Okonkwo’s second wife, who left her husband for Okonkwo. She has borne 10 children and lost all but one, her daughter Ezinma. Her love for Ezinma leads her to stand up to Okonkwo on occasion.

Ezinma

She is Okonkwo’s favorite child, beautiful and connected to her father in a deep way. Only she can understand him and his moods. Her only flaw, in his eyes, is being a girl

Ikemefuna

A boy from a neighboring clan who is seized by Umuofia warriors. He lives with Okonkwo’s family as a peace offering, and is a more satisfying son to Okonkwo than Nwoye.

Mbanta

The home village of Okonkwo’s mother; he and his family are banished here for seven years after Okonkwo accidentally kills someone.

Nwoye

Okonkwo’s eldest son shows every sign―so far as Okonkwo is concerned―of being a lazy, weak man like Unoka. Beaten and belittled by his father, Nwoye will become a prime target for conversion by the English missionaries.

Nwoye’s mother

Okonkwo’s first wife, whose name is not told to the reader. She, unlike her husband, understands the value of pity, gentleness, and forgiveness. Her stories instruct and delight the children.

Obierka

A thoughtful member of the clan who is Okonkwo’s best friend. He tries to help Okonkwo navigate the troubles that come to him, and is left cleaning up after Okonkwo’s catastrophic end.

Ogbuefi Ezeudu

The highest-ranking man in the village, and holder of three titles―a great rarity.

Okonkwo

This self-made man has worked his way up from poverty and, as he sees it, freed himself from the disgrace of having a lazy, “feminine” father. While Okonkwo possesses real virtues of hard work, far-sightedness, devotion to his clan, and love, these co-exist uneasily with impulses of fear, pride, and impatience.

Mr. Smith

The far more zealous Smith replaces Brown and leads his new converts on a full-scale war of ideas against the village.

Umuofia

The village that Okonkow lives in. It is known for its willingness to start or go to war.

Unoka

Okonkwo’s father, a gentle musician who left his family poor and in debt at his death. He held no titles of rank in the village―driving Okonkwo to vow that he would hold many.