Join us for conversations that inspire, recognize, and encourage innovation and best practices in the education profession.

Available on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, Google Podcasts, and more.

What do we owe the gods? What do we deserve from them? Is it folly to insist on order and decorum in light of our true passions and furies, often so far from orderly? What decides our fate? Who are we?

The Bacchae’s tragic arc unfolds these questions and pulls all of us into its thrall, as surely as Pentheus, the mortal man, is tempted by the very urges he takes up arms against. It is a spell cast across 2500 years, still potent, still disturbing.

“And at the end of the play, I think one of the most poignant moments is when Cadmus says to the god Dionysus, ‘I know we erred, but you are too cruel, you punished us too much.'”

BCE

600s

The Greek Festival Dionysia are underway; these festivals include annual or semi-annual performances of tragedies (and later comedies)

550

The beginning of the era of classic Greek theater

480

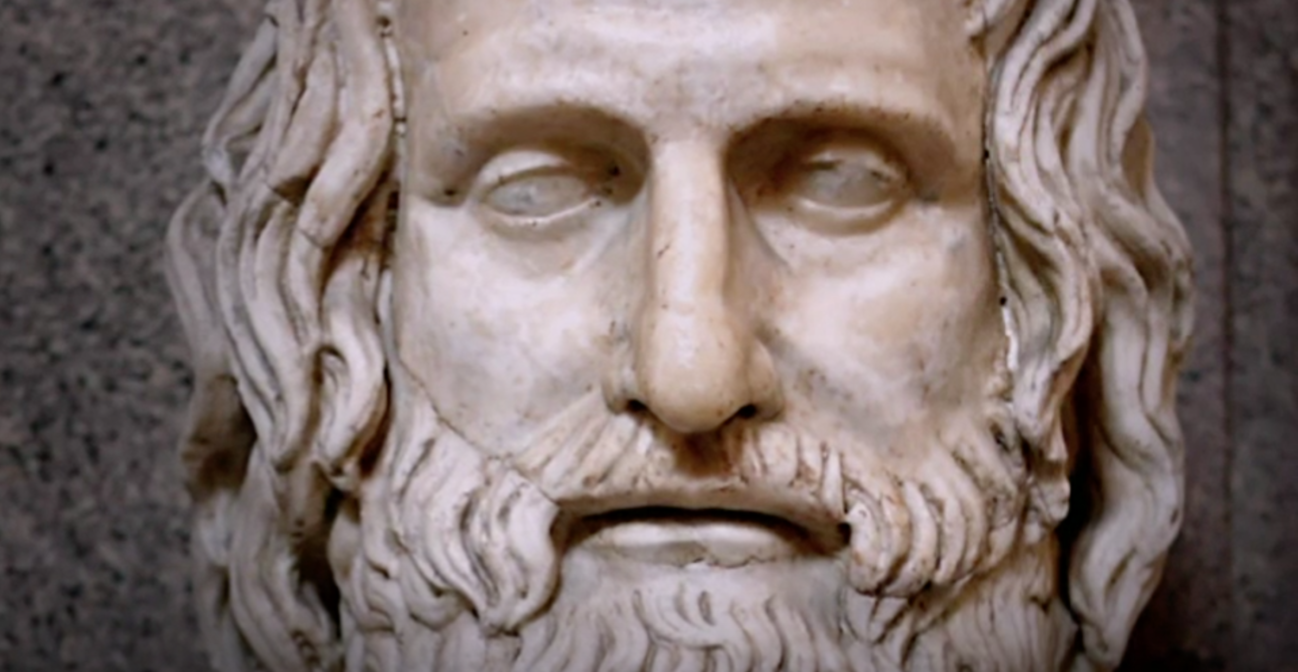

The birth of Euripides

455

The likely date that Euripides’ first play, Rhesus, was performed

431

The first performance of Euripides’ Medea

406

The death of Euripides

406-405

The first posthumous presentation of The Bacchae

220

The end of the era of classic Greek theater

So what do you need to know about The Bacchae before you read it?

The Bacchae is one of the best-known works from the golden age of Greek drama, the fifth century BCE, when plays were performed in large open air theaters as part of seasonal festivals called Dionysia (named after the Greek god who is the central character in this play). The audience for these plays was very large—the theaters could seat over 15,000, and likely included women and slaves. The festivals went on for many days, and people would see tragedies and comedies, one after another, tales of gods and men, under the Mediterranean sky.

In today’s theater, unless you go to see a revival or a very famous play, you expect to be surprised by the plot. You want to wonder what will happen, what’s coming next. In ancient Greece, the underlying stories came from the tales of Greek gods and famous early heroes, and they were generally common knowledge—viewers already knew what was going to happen. What a writer and performers did with a story was what mattered.

The stagings had costumes, but little scenery in the modern sense. A building in the back of the stage, the skene, served as a fixed structure for entrances and exits. Without sets, the words the characters spoke created the entire scene, and they did so magnificently. The performers wore masks that both amplified volume and expressiveness, as well as exaggerating facial expressions. A small number of actors, generally three, and all of them men, played all of the roles.

Although the stage was spare in the Greek theater festivals, there was one spectacular effect: the “machina,” a mechanical device like a crane that lowered or raised a character, usually a god, at the climax of a play. This device was known as the deus ex machina, or “god from the machine.” Euripides often relied on this for a big finale in his works, and the deus ex machina is used at the end of The Bacchae, when Dionysus appears in his full godlike form for the first time.

A final note about reading a play: it’s helpful to remember that this text is meant for live performance by actors. In addition to creating the images of the play in your mind, you may wish to speak—or even try to sing or chant—the speeches aloud to get a sense of how they might have been performed, or even better, ask friends to recite them with you. Remember, you need only three people to play all of the characters.

The language of the play is Greek; the rhythm comes from long and short as well as stressed and unstressed syllables, which create the sound and poetry of the lines. Helene Foley mentions one example of these rhythms in the video, the “ionic dimeter” of i-te bac-chae, i-te bac-chie, short-short-long-long, short-short-long-long, and making for a powerful chant, “Go Bacchae!, Go Bacchae!”

Very little of the language of Greek drama is naturalistic; no one really speaks like that in everyday life. This formal nature of the language in Greek drama was no more unusual to its original audiences than hearing a play or concert in modern musical rhythms is for us today. Both present kinds of language that are not used in everyday speech, but have expressive power when used in drama.

Agave

The mother of Pentheus and the aunt of Dionysus (Semele, Dionysus’ mother, was Agave’s sister).

Cadmus

Father of Agave, Grandfather of Pentheus and Dionysus.

Dionysus

The god of fertility and power of nature, Dionysus causes fruit to ripen and the sap to rise in trees. He is also known as Bacchus, the god of wine. Dionysus was the son of the god Zeus and Semele, a mortal. He is the leader of the Bacchae, his female followers, who worship him.

Pentheus

The young king of Thebes, (and cousin of Dionysus) who does not recognize Dionysus’ godhood.

Teiresias

A prophet of Thebes and friend of Cadmus.

The Bacchae

The female followers of Bacchus/Dionysus.

The Chorus

Followers of Dionysus who have traveled with him from Asia Minor; they comment on the action but do not take part in it.

Agave

The mother of Pentheus and aunt of Dionysus, who did not believe Dionysus was really the son of Zeus or a god himself; now, as the play begins, Agave is in thrall to Dionysus.

Asia Minor

This term is used to describe Western modern-day Turkey, the peninsula that is bounded by the Black Sea, the Aegean Sea, the Sea of Marmara, and the Mediterranean Sea.

Bacchae

(or Bacchants) The all-female followers of Bacchus/Dionysus.

Cadmus

The Father of Agave and grandfather of Pentheus and Dionysus.

Chorus

This convention of Greek theater is a group of performers who sing and dance, commenting on the action, and sometimes playing a more substantive role.

Dionysus

The god of fertility and power of nature. Dionysus causes the fruit to ripen and the sap to rise in trees; also known as Bacchus, the god of wine. Dionysus is the leader of the Bacchants, or Bacchae, his female worshippers. He has come to Thebes after establishing his cult of worship in the East.

Euoi

The cry of ecstasy associated with bacchic celebrations.

Euripides

One of the three great tragic playwrights of Ancient Greece, author of The Bacchae. He lived c. 480-406 BCE.

Faun-Skin

The traditional clothing of the Bacchae, both female, and on occasion, male (for instance when Cadmus and Teiresias appear in faun-skin).

Lydia

An ancient kingdom in western Asia Minor, passed through by Dionysus and his followers.

Maenads

Yet another term for the female followers of Bacchus; in this play, the crazed Theban women have been made mad by the god.

Messengers

In Greek theater, messengers were a conventional way to relate action that was key to the play but was not portrayed on stage. Messengers arrive and deliver vivid, and often somewhat formal, speeches.

Mount Cithaeron

A mountain near Thebes where the rites of Dionysus take place.

Ode

A poetic form that organizes sections of a play. Greek dramatists used choral odes in plays, with standard elements such as prelude, strophe, and antistrophe.

Pentheus

The young king of Thebes, (and cousin of Dionysus) who does not recognize Dionysus’ godhood.

Semele

Agave’s sister, and Dionysus’ mortal mother, who is burned to death by Zeus when she demands that he appear in his full godhood. The unborn Dionysus is saved and sewn into the thigh of Zeus. It is Dionysus’ anger over his aunt’s and Pentheus’ failure to acknowledge that he is Semele’s child by Zeus, and therefore a god, that triggers the action of the play. Semele’s grave appears in the play.

Sparagmos

The Dionysian ritual in which a living animal would be sacrificed and dismembered.

Stasimon

A choral song performed from a stationary part of the theater, such as the orchestra.

Stichomythia

A conversation between characters that proceeds in single sentences. Stichomythia is an aspect of a play that contrasts with longer narrative speeches, such as those from messengers or odes from the chorus.

Thebes

The Greek city in which the action of The Bacchae, and many other classic Greek dramas, takes place.

Thyrsus

(or Thyrsos) A staff of fennel. Like the fawn-skin, a typical attribute of the Bacchae, used in worship as well as to create magic events.

Zeus

The chief Greek god, father of Dionysus.