Join us for conversations that inspire, recognize, and encourage innovation and best practices in the education profession.

Available on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, Google Podcasts, and more.

The region where The Thousand and One Nights originated as oral tales.

© 2010 Map Resources, All rights reserved.

The stories in The Thousand and One Nights have traveled the world repeatedly over the centuries. But this region is where they originated, first told by storytellers in the 600s-900s CE in Iran, Saudi Arabia, and India. They journeyed to Baghdad, capital of the Abbasid Empire, and spread west from there. Even within the empire, the stories were changed and amplified. When this empire broke up, the stories remained.

Folktales are told in Persia, Arabia, and India that will form the basis of The Thousand and One Nights.

The tales reach Baghdad, capital of the Abbasid Empire.

Haroun al-Rashid rules as the third Caliph and greatest leader of the Abbasid Empire.

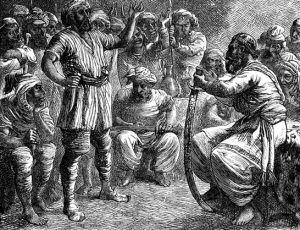

Al-Rashid appears as a character in some of the tales of The Thousand and One Nights.

The Abbasid Empire reaches its peak of power.

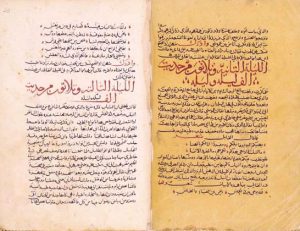

The collection of stories that became Alf Laylah wa Laylah (The Thousand and One Nights) was written down, most likely in Syria.

The Syrian archetype copy was written down.

The tales circulate throughout the Middle East, including Cairo, where copyists record the tales. These versions become the basis for later editions.

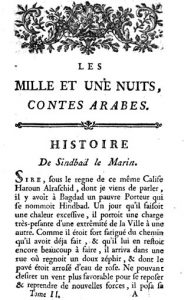

French translator Antoine Galland is born.

Galland’s pathbreaking translation is published.

Edward Lane’s English translation is published.

Lane uses the Bulaq, and edits the stories to make them “decent.”

Richard Burton’s English translation is published.

Burton uses the Bulaq, and adds florid language, together with copious ethnographic notes, using the tales to explain Islam and Middle Eastern customs.

Muhsin Mahdi, an Iraqi scholar of Arabian history, literature, and philosophy publishes a definitive modern edition of the Syrian archetype.

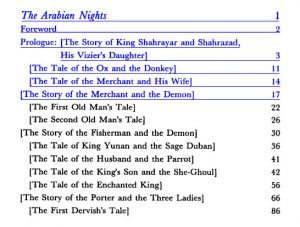

Husain Haddawy publishes a collection of stories based on Mahdi’s translation called The Arabian Nights.