Join us for conversations that inspire, recognize, and encourage innovation and best practices in the education profession.

Available on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, Google Podcasts, and more.

If you want to tell a story of murder, war crimes, kidnapping, slavery, rape, and religious hypocrisy, how do you do it? How can you make such events bearable—and even enjoyable—to read? Do you present the facts plainly, almost like reporting, or do you develop fictional characters and events to represent all these things and engage your readers’ sympathy? If you are Voltaire, you do both at once.

Candide is at once an obvious work of fiction, with gross exaggerations and impossible plot twists, and also a cold-blooded report of the crimes humans commit against each other for a variety of reasons. You could go through Candide with a pencil and mark events in each chapter that really happened—the Thirty Years’ War, the Lisbon earthquake, African slavery in the New World—and then go through the book again and mark everything that is impossible, from a man surviving three executions, including burning at the stake, to travels to a mystical hidden kingdom, where the streets are lined with jewels and the sheep are red.

The fictional elements, be they comic relief or unattainable paradise, keep you reading through an otherwise unbearable story.

“The great irony then is, the real, mature wisdom Candide comes to is wealth has not made him happy. [Nor has] success, finding love, getting the girl of his dreams. The only possibility he has of happiness is being in the real world, connecting himself to the earth represented by this small farm and doing real work, simple, real work on a daily basis.”

CE

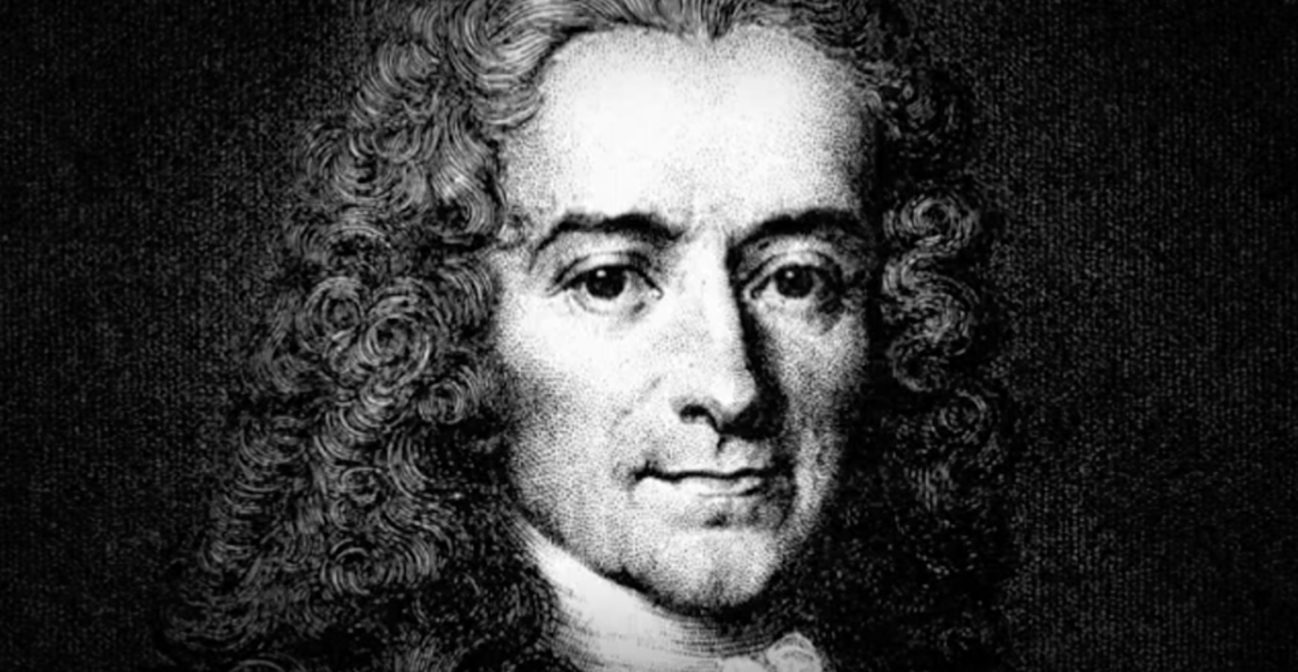

1694

Voltaire is born in Paris, France to a wealthy lawyer and the daughter of a member of Parliament; his given name is François-Marie Arouet.

1717-8

Arouet is imprisoned in the Bastille prison in Paris, falsely accused of writing a satiric attack on the king. On his release, he publicly adopts the name Voltaire.

1734-50

He lives in exile on the border of the French province of Lorraine, studying Newtonian physics and contemporary philosophy.

1759

Candide is published.

1778

Voltaire returns to Paris to see the performance of his latest play, Irene. He is received as a hero. He dies on May 30.

“Voltaire” was the pen name of François-Marie Arouet, a French writer who spent much of his life outside of France, banished for his satires and attacks on the government and the royal family. His 1759 novel Candide tells the story of an endlessly optimistic young man who goes through the most terrible adventures, and witnesses those of his friends, only to wind up safe and contented, though in a strange land.

Just as Gabriel García Márquez presents a “magical realism” in One Hundred Years of Solitude, in which events we would call unreal or impossible mix freely with what we would identify as real, so Voltaire presents a world made up of extremes of bitter realism and shocking fiction, and makes it hard to separate the two. Candide presents real events and lets fictional characters tell the truth about them. For example, when Candide goes to Lisbon and the city is destroyed by a terrible earthquake, some survivors are picked out by the Catholic church for burning. They are human sacrifices who will atone for the sin that must have caused the quake. A real church leader in Lisbon would not have openly said that “burning a few people alive by a slow fire, and with great ceremony, is an infallible preventive of earthquakes.” He would have had a complex theological argument in favor of the burnings that never used the word “burning”. But in Candide, the religious leader says this, bluntly and clearly, and in so doing, strips the action and the church of all justification. In Candide, it’s as if every character has been given a truth serum which makes him or her tell all, honestly, without shame or fear.

In this way, Candide goes beyond satire to a philosophical examination of the human mind and our ability to deny reality. Why do we use lies to support injustice? Why do we turn a blind eye to hypocrisy? Why would we rather live in a world of criminal unfairness than a better world—for we all have chances to change things. Voltaire shows us that just like Candide, who cannot stay in the paradise of El Dorado because he is tied to a part of the fallen world, we all fail in our opportunities to make this world indeed the best possible one.

Candide was written in French, Voltaire’s native language. It was translated into English the same year it was published in French, and titled Candide: or, All for the Best. An Italian translation also came out in 1759. In 1762 another English translation by the novelist Tobias Smollett appeared called Candide: or, The Optimist; Smollett was just the first of many writers to be influenced by the work. It has been translated into every major world language.

Brother Giroflé

Forced to become a monk in order for his elder brother to inherit the family wealth, Giroflé is a model of inner misery amid seeming happiness.

Cacambo

A product of the Spanish colonization of the Americas, Cacambo is the son of an Indian woman and a half-Indian, half-Spanish man. He goes through as many roles and adventures as Candide, and serves as Candide’s friend and valet.

Candide

An Everyman figure, naïve and a victim of experience, Candide is completely vulnerable to the criminals, hypocrites, liars, and fiends of the world, yet is redeemed by his love for Cunégonde and his undying optimism.

Cunégonde

Daughter of a German baron in Westphalia, Cunégonde is tossed from place to place, continent to continent, by a series of men who claim her. She remains virtuous in spirit throughout, and a beacon to Candide.

The Jesuit Colonel

Cunégonde’s brother falls into the Jesuit priesthood and religious war as accidentally as his sister falls into sexual slavery or Candide falls into prison. His obstinate class prejudice leads him to oppose Candide’s marriage to his sister, with almost fatal results.

The King of El Dorado

The only successful, decent, appealing man of power in the novel. His complete isolation from the rest of the world is probably what makes his virtue possible.

Martin

This philosopher has rationally allowed misfortune to make him pessimistic. He is therefore honest and engaging, and Candide keeps his company through the end of the book.

The Old Woman

Her life parallels Cunégonde’s, in that the Old Woman was once a Princess who was sold into slavery several times, taken advantage of by many men high and low, and winds up working for the moneylender Don Issachar, who buys Cunégonde.

The Negro Slave

A slave whom Candide encounters in the South American colony of Surinam; the horror of this man’s life underscores the stark reality beneath the comic exaggerations of Candide’s adventures.

Pangloss

A peddler of worthless posturing masquerading as philosophy. Pangloss thinks the philosopher Leibniz said that everything happens for the best, and he sticks by this ignorant misinterpretation throughout all the horrors of the book.

Paquette

Chambermaid to Cunégonde’s mother; her relationship with a priest leads to her banishment from Westphalia. She becomes an official prostitute, as opposed to the unofficial prostitution of Cunégonde.

Brother Giroflé

Forced to become a monk in order for his elder brother to inherit the family wealth, Giroflé is a model of inner misery amid seeming happiness.

Cacambo

A product of the Spanish colonization of the Americas, Cacambo is the son of an Indian woman and a half-Indian, half-Spanish man. He goes through as many roles and adventures as Candide, and serves as Candide’s friend and valet.

Candide

An Everyman figure, naïve and a victim of experience, Candide is completely vulnerable to the criminals, hypocrites, liars, and fiends of the world, yet is redeemed by his love for Cunégonde and his undying optimism.

Cunégonde

Daughter of a German baron in Westphalia, Cunégonde is tossed from place to place, continent to continent, by a series of men who claim her. She remains virtuous in spirit throughout, and a beacon to Candide.

El Dorado

The mythical South American paradise where there is no crime or religion or injustice, gold and jewels take the place of mud and rocks in the streets, no one goes hungry, and no one is ever sad. It is the opposite of everything that real human civilization offers. Candide is well-treated here, but ultimately leaves it to find Cunégonde.

The Jesuit Colonel

Cunégonde’s brother falls into the Jesuit priesthood and religious war as accidentally as his sister falls into sexual slavery or Candide falls into prison. His obstinate class prejudice leads him to oppose Candide’s marriage to his sister, with almost fatal results.

The King of El Dorado

The only successful, decent, appealing man of power in the novel. His complete isolation from the rest of the world is probably what makes his virtue possible.

Martin

The philosopher Martin travels with Candide for much of the story, serving as his companion and conversational foil. Martin has rationally allowed misfortune to make him pessimistic. He is therefore honest and engaging.

The Old Woman

Her life parallels Cunégonde’s, in that the Old Woman was once a Princess who was sold into slavery several times, taken advantage of by many men high and low, and winds up working for the moneylender Don Issachar, who buys Cunégonde.

The Negro Slave

A slave whom Candide encounters in the South American colony of Surinam. The horror of this man’s life underscores the stark reality beneath the comic exaggerations of Candide’s adventures.

Pangloss

The tutor of Candide and Cunégonde, Pangloss thinks that everything happens for the best. He stubbornly maintains this view throughout all the horrors of the book.

Paquette

Chambermaid to Cunégonde’s mother; her relationship with a priest leads to her banishment from Westphalia. She becomes an official prostitute, as opposed to the unofficial prostitution of Cunégonde.

Westphalia

Candide’s home, a small principality in what is today modern Germany. In the novel it stands in for the average European society.