Join us for conversations that inspire, recognize, and encourage innovation and best practices in the education profession.

Available on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, Google Podcasts, and more.

This final unit presents ways to integrate the reading and writing methods covered in the previous units into classroom instruction. It also includes ways of considering student progress toward goals over the course of an academic term. Taken together, the sections in this unit provide guidelines for engaging students in analytical and critical thought about topics in history and social studies. Such analytical and critical thought is applicable beyond history and social studies instruction—from understanding sources of information on the Internet to critiquing the positions of interest groups.

Video and Reflection: Revisit Reading and Writing in History as an example of bringing reading and writing together in studying history. You may want to take notes on the questions below.

Developing historical thinking skills is not a one-time lesson, but rather is something that should be engaged in throughout the school year in order to build deeper understanding and critical thinking. Inquiry is a critical process that requires long-term practice. Therefore, it is important to remember to begin by selecting goals (whether from the NCSS C3 Framework, Common Core, or state content/skill standards) for the entire year and focus on those goals consistently throughout the year. Developing students’ literacy skills requires continued attention over the long term and is not accomplished after one or two lessons. In order to measure student progress toward learning goals, teachers should design ways for tracking student progress.

Video and Reflection: Watch History in the Real World: A Documentary Filmmaker as an example of how to integrate reading, writing, and history/social studies in the real. You may want to take notes on the questions below.

Video and Reflection: Now watch Creating a Classroom Culture as an example of using standards to track student progress. You may want to take notes on the questions below.

A few scholars and researchers have undertaken work that aims to incorporate disciplinary literacy practices into classroom instruction. Abby Reisman at Stanford has designed the document-based lesson, or DBL, as a frame for a predictable and repeatable sequence that engages students in the process of historical inquiry. This type of lesson has been used successfully in diverse classrooms to improve high school students’ historical thinking, reading, and knowledge as well as their reading comprehension.

In another research project, Chauncey Monte-Sano of the University of Michigan, Susan De La Paz of the University of Maryland, and Mark Felton of San Jose State University added writing to the elements of a DBL. Their project, taken up in diverse middle school classrooms, showed that such lessons improve the argument and historical writing of students.

The DBL with incorporated writing brings together the various aspects of disciplinary inquiry that have been covered in the units of this course. The primary components of such a DBL with writing are:

In a DBL with writing, students take part in an open-ended investigation while connecting content knowledge with disciplinary inquiry into the content. They learn that facts are constructed through interpretation and not memorized. By learning this, students themselves are encouraged to make their own interpretations about the sources they read. DBLs naturally integrate reading, writing, and thinking. In short, the DBL is an investigation by design; something with which teachers can develop their own style of materials for use in their classrooms.

Explore: View Rosa Parks: Writing Assignment [PDF] for an example of how to incorporate writing into a DBL.

Video and Reflection: Revisit Reading Like a Historian as an example of a document-based lesson. You may want to take notes on the questions below.

When designing an investigation, one of the most important considerations a teacher needs to make is the alignment among all the materials that students will use. Of primary concern is the alignment between the essential question being asked and the sources that students will use as evidence for making claims in response to the essential question.

As mentioned in Unit 5, Section 5, here are some criteria for deciding what makes for good essential questions. The best questions to guide inquiry:

Another important issue is whether multiple perspectives are conveyed in a document set or whether the set is skewed toward one perspective. As a way of monitoring issues of alignment and equitable perspectives, the following questions can be asked:

Discussion can help students make sense of the work they are doing in the historical inquiry, as it provides an opportunity for students to collectively develop their knowledge and interpretations, build on others’ ideas, and receive feedback about their work with texts and the writing process. Discussions can take place both with student-to-student conversations and those that take place as a whole class.

Teachers can use certain discussion moves that clarify what students are thinking, extend the conversation to other students that push students’ thinking, and hold students accountable to what the text or other students might be saying.

Explore: Check out the following documents about different discussion methods.

Reflect: How might these types of discussions reinforce the use of literacy skills and inquiry in the social studies classroom?

Explore: Review Questioning the Author: Discussion Moves [PDF] for a list of dialogic moves that teachers can use in facilitating classroom discussions.

Reflect: How might these different discussion moves support students and develop their thinking as they work with sources in the classroom?

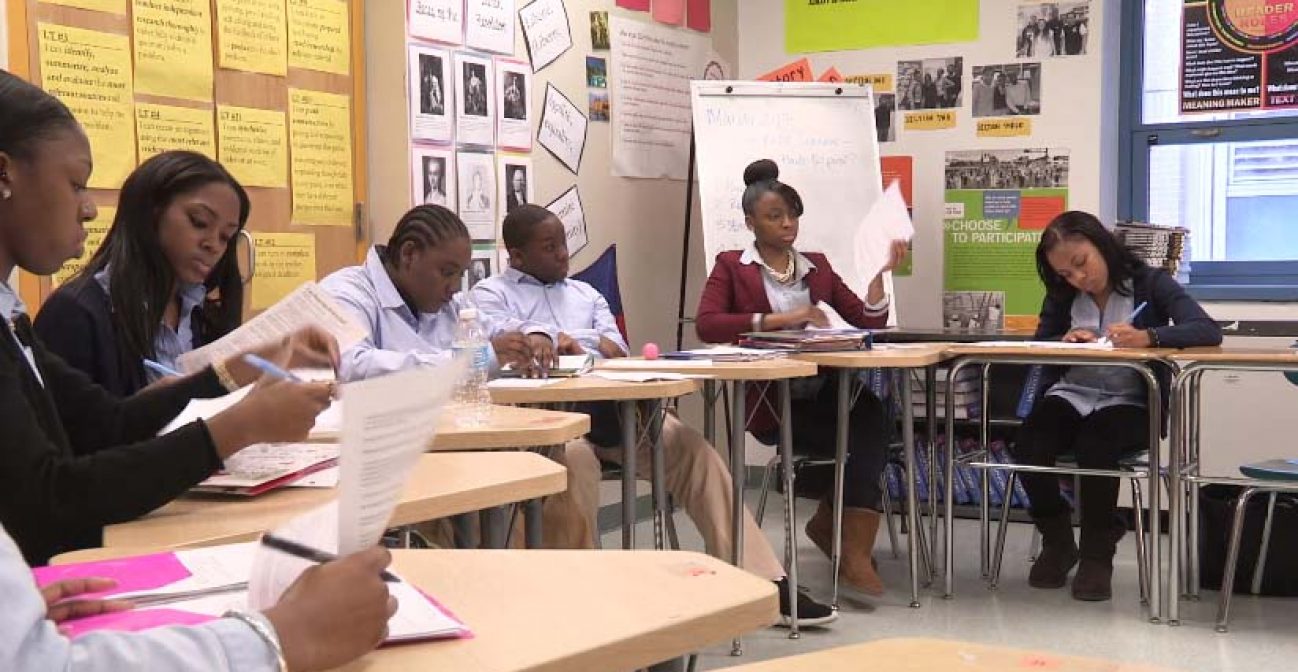

Video and Reflection: Watch Facilitating a Socratic Seminar and Designing the Classroom to Support Understanding as examples of using discussion to support reading and writing. You may want to take notes on the questions below.

Finding and selecting texts is time-consuming, but it gets easier. Some of the first places to turn to in locating primary sources are the National Archives and Library of Congress. Each of these institutions has done extensive work in putting together sets of primary sources and creating platforms for searching for additional sources. See References and Further Reading for more examples.

Other libraries are able to assist in finding primary sources. This may take more time to research, but university libraries and state archive libraries can be good repositories for finding primary sources for state history and social studies.

A general online search can also reveal primary sources. However, as with all things on the Internet, it’s important to view things critically. Look at the creator or author of a source in the same way that you do when reading the source itself. There are certain search criteria that can be used in trying to find reputable sources. These include searching by specific sites. For example, when searching Google for sources about the Great Depression, you can type into the search bar “Great Depression site:.edu” and reveal search results that are relevant to the Great Depression but are located only on higher education websites. A more specific search of a certain website is also possible. For example, a search of “Dust Bowl site:loc.gov” will reveal results relevant to the Dust Bowl but only from the Library of Congress’s website.

The materials in this course explored the role of disciplinary literacy in history and why it is important to engage students in these disciplinary literacy practices. Unit 5 began with an introduction to key concepts and tools that promote disciplinary literacy, such as using investigation and interpretation to promote inquiry, developing background knowledge, and using historical sources to back up claims. The next units focused on strategies for reading and analyzing texts and argument writing as a process in history. The course concluded with suggestions of various methods to support the integration of reading and writing practices into classroom instruction.

By teaching with practices that approximate the work of historians—including reading, writing, and thinking practices—history and social studies teachers can support students in thinking critically about disciplinary content in the classroom. However, these literacy practices that engage students in analytical and critical thought about history aren’t limited to the classroom. They can also prepare and inspire students to participate in future studies or careers and to become well-informed citizens.

Beck, I., & McKeown, M. (2006). Questioning the author. New York: Scholastic.

Caron, E. J. (2005). What leads to the fall of a great empire? Using central questions to design issues-based history units. The Social Studies, 96(2), 51–60.

Collins, A., Brown, J. S., & Holum, A. (1991). Cognitive apprenticeship: Making thinking visible. American Educator, 15(3), 6–11.

Counsell, C. (1997). Analytical and discursive writing. London: Historical Association.

Historical Thinking Matters. http://www.historicalthinkingmatters.org.

Kiuhara, S. A., Graham, S., & Hawken, L. S. (2009). Teaching writing to high school students: A national survey. Journal of Educational Psychology, 101(1), 136.

McTighe, J., & Wiggins, G. P. (2013). Essential questions: Opening doors to student understanding. Alexandria, VA: ASCD.

Michaels, S., O’Connor, M. C., Hall, M. W., & Resnick, L. B. (2010). Accountable Talk sourcebook: For classroom conversation that works. Pittsburgh, PA: University of Pittsburgh Institute for Learning, 1–4.

Monte-Sano, C., De La Paz, S., & Felton, M. (2014). Reading, writing, and thinking about history: Teaching argument writing to diverse learners in the Common Core classroom, grades 6–12. New York: Teachers College Press.

Monte-Sano, C. (2012). What makes a good history essay? Assessing historical aspects of argumentative writing. Social Education, 76(6), 294–298.

Monte-Sano, C. (2012). Build skills by doing history. Phi Delta Kappan, 94(3), 62–65.

National History Education Clearinghouse. http://www.teachinghistory.org.

Paxton, R. J. (1997). “Someone with like a life wrote it”: The effects of a visible author on high school history students. Journal of Educational Psychology, 89, 235–250.

Reisman, A. 2011. The “document-based lesson”: Bringing disciplinary inquiry into high school history classrooms with adolescent struggling readers. Journal of Curriculum Studies, 44(2), 233–264.

Wiggins, G., & McTighe, J. (2005). Understanding by design. Alexandria, VA: ASCD.

Wineburg, S. S. (1991). Historical problem solving: A study of cognitive processes used in the evaluation of documentary and pictorial evidence. Journal of Educational Psychology, 83, 73–87.

Wineburg, S. S. (2001). Historical thinking and other unnatural acts: Charting the future of teaching the past. Philadelphia: Temple University Press.

Wineburg, S., & Martin, D. (2009). Tampering with history: Adapting primary sources for struggling readers. Social Education, 73, 212–216.

Wineburg, S. S., Martin, D., & Monte-Sano, C. (2012). Reading like a historian: Teaching literacy in middle and high school history classrooms. New York: Teachers College Press.

Sources for locating primary sources:

For an example of students “doing” history: Foderado, L. South Bronx students may have found site of slave burial ground.New York Times, January 25, 2014.

The 2014 book Reading, Thinking, and Writing About History: Teaching Argument Writing to Diverse Learners in the Common Core Classroom, Grades 6–12 (Common Core State Standards for Literacy) by Chauncey Monte-Sano, Susan De La Paz, and Mark Felton provides examples of two 8th-grade students’ argument writing in history over the course of a year.

Library of Congress’s Supporting Inquiry with Primary Sources.

Lessons from the National History Education Clearinghouse that use the textbook and primary sources.

A lesson from Stanford’s Reading Like a Historian website that includes both primary and secondary sources.

The videoWhy Historical Thinking Matters provides an overview of sourcing.

The Beyond the Bubble website, sponsored by the Stanford History Education Group, provides a variety of assessments linked to the study of sources.

Stanford’s Reading Like a Historian website includes numerous curricular examples of document-based lessons.