Join us for conversations that inspire, recognize, and encourage innovation and best practices in the education profession.

Available on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, Google Podcasts, and more.

Program 4: The Coming of Independence

Donald L. Miller, Pauline Maier and Waldo E. Martin, Jr

Introduction

Narrator: America in 1763, not yet a nation.

Miller: Are we dealing with a nation that’s becoming more alike, or is it becoming more different at the same time?

Maier: Well, I think we started out as different as we could possibly be.

Narrator: The beginning of the American Revolution — 13 colonies under the British flag.

Maier: They see their future as British.

Narrator: But the bond is severed and Americans declared their independence in action and in their written documents.

Martin: These are not dead documents.

Maier: And these documents changed in meaning and in their significance as a result of this conflict.

Narrator: Today on A Biography of America, “The Coming of Independence.”

The Colonies Under British Rule

![[Picture of Professor Maier]](https://www.learner.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/a-biography-of-america-the-coming-of-independence-4_maier.jpg)

Maier: The British colonists saw the year 1763 as a great watershed in American history. In the past, a great semi-circle of “Catholic enemies” had hemmed them in from French Canada and Louisiana on their north and west to Spanish Florida in the south. But in 1763, the Peace of Paris gave all the lands between the Atlantic Ocean and the Mississippi River to Britain’s young King George III. That change, the colonists assumed, would bring peace and security beyond anything they or their parents or their parents’ parents had known. And now nothing would keep them from spilling beyond the Appalachian Mountains.

In the wave of patriotism that swept the colonies after the French and Indian War, no one doubted that the America of the future would be British. At the time, in fact, the various colonies had no ties with each other except through London and their shared British identity.

The Americans were particularly proud of being governed under the “British constitution,” that is, Britain’s form of government, which divided power among the King, Lords, and Commons, and which they, like many enlightened Europeans, considered the best mankind had ever devised for the protection of liberty.

Affection reinforced the imperial bond. One set of colonists after another testified that their hearts were “warmly attached to the King of Great Britain and the royal family.”

The mystery is why, only thirteen years later, they declared their Independence. That mystery is not ours alone. It was the colonists’ too. As events unfolded, they wondered at the unexpected course their history was taking, and sought explanations.

Taxation and the Stamp Act

The conflict between Britain and her American colonists began over taxes. The war left Britain with a large debt and new financial obligations. A massive Indian uprising showed that the Crown had to keep an army in America. The British restored peace and then, to prevent further trouble, excluded settlers from lands beyond a line that ran north and south through the Appalachian mountains.

![[Picture of a stamp]](https://www.learner.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/a-biography-of-america-the-coming-of-independence-c004.jpg)

Not only was Britain blocking the colonists’ westward expansion; it wanted them to help pay for its army in America. First they had Parliament put new duties on molasses imported into the colonies from the non-British West Indian Islands. That awoke little opposition. But when the King’s minister announced plans for a “stamp tax” on American legal documents, newspapers, pamphlets, and items such as dice and playing cards, all hell broke loose.

Never before had the Parliament laid a direct tax on the colonists. In Britain, taxes were considered “free gifts of the people” that could be raised only with the people’s consent or that of their representatives. Since the colonists elected no members of the House of Commons, they argued, Parliament had no right to tax them. Even a small tax was dangerous.

![[Picture of a cartoon protesting the Stamp Act]](https://www.learner.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/a-biography-of-america-the-coming-of-independence-c015.jpg)

Once Parliament established its right to tax the colonists, it would tax them to death since by taxing the Americans, members of Parliament reduced their own tax burden and that of their constituents. The Americans made their case in petitions that Parliament refused even to receive. Then, after all else failed, they found a way to prevent the Stamp Act from going into effect.

On the morning of August 14, 1765, an effigy of the Massachusetts Stamp Distributor, Andrew Oliver, appeared hanging from a tree in the center of Boston. All day goods brought into town from the countryside had to be “stamped” by the effigy. At night a crowd took it down, paraded the effigy through town, then burned it in a great bonfire with materials torn from a supposed “stamp office” that Oliver was building. Later, part of the crowd attacked Oliver’s home. Fearing more of the same, he resigned his office the next day, and no one was willing to take his place.

That meant the Stamp Act could not go into effect in Massachusetts since there was no one to distribute the stamps. Soon stampmen in one colony after another resigned to avoid Oliver’s fate. Then groups called the Sons of Liberty appeared to coordinate opposition to the Stamp Act across colony lines. The colonists also boycotted certain British imports. Parliament gave in. It repealed the Stamp Act, but only after declaring that it had a right to bind the colonies “in all cases whatsoever.” A year later, it tried to raise revenue through new duties on paper, glass, and tea. If that’s how colonists preferred to give money to the Crown, the King’s new minister, Charles Townshend, argued, let them have their way.

![[Picture of John Dickinson]](https://www.learner.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/a-biography-of-america-the-coming-of-independence-c019.jpg)

But now a series of newspaper essays entitled “Letters from a Farmer in Pennsylvania” urged the colonists to resist. They were, in fact, written by a mild-mannered lawyer named John Dickinson, a man of property with Quaker connections who was dead set against violence. Duties meant to raise revenue were taxes, he said, and so every bit as dangerous as the Stamp Act. But “we cannot act with too much caution,” he wrote, because anger had a way of producing anger, and could cause a separation of the colonies from Britain. “Torn from the body, to which we are united by religion, liberty, laws, affections, relation, language and commerce” he said, “we must bleed at every vein.”

Dickinson recommended peaceful forms of opposition, such as non-importation associations, if the colonists’ petitions went unanswered. Dickinson’s “Farmers’ Letters” were copied from one newspaper to another. And everywhere the colonists said he had expressed their position perfectly. They also followed his advice and cut back imports until, again, Parliament gave in. In 1770, it repealed all the new duties except the one on tea.

The Boston Massacre

By then, however, many colonists’ old confidence in the British government was pretty much gone. Taxes were not the only reason. In 1768, the Crown had sent two regiments of troops to Boston to support royal officials there. Bostonians said the troops were unnecessary and, like all Englishmen, distrusted governments that used “standing armies” against their own people. Freemen, they said, are not governed at the point of a gun.

![[Picture of Paul Revere's painting 'The Boston Massacre']](https://www.learner.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/a-biography-of-america-the-coming-of-independence-c029.jpg)

It seemed as if the soldiers and civilians were always scuffling with each other. Finally, on March 5, 1770, a contingent of troops fired into a crowd, killing five people. Paul Revere, a local silversmith and patriot, memorialized the “Boston Massacre” with one of the most famous prints of the era. It shows redcoats willfully shooting unarmed civilians.

Another smoking gun protrudes from a window behind the soldiers, in a building labeled “Butcher’s Hall.” Was its trigger perhaps pulled by a hated customs man? Nowhere to be seen are the snowballs, some with rocks inside, that crowd members threw at the soldiers. Nor is there any indication that Bostonians provoked the soldiers by shouting “fire! fire!,” which they thought the troops could not do without the permission of town officials. The print, in short, gave only one side of the story.

The Boston Tea Party

Trouble began again after Parliament tried to help the East India Company sell tea in the colonies at a price lower than that of smuggled tea. It refused, however, to remove the old duty, which, from the colonists’ perspective, “poisoned” the East India Company’s cheap tea.

Again they resisted, but in as peaceful a manner as they could. Colonists in New York and Philadelphia, for example, convinced the captains of tea ships to turn around and take their cargoes back to England without paying the tea tax.

![[Picture of the Boston 'Tea Party']](https://www.learner.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/a-biography-of-america-the-coming-of-independence-c033.jpg)

In Boston, however, the tea ships entered the harbor before the opposition organized. Townsmen spent the next twenty days trying without success to get clearances so the ships could go back to sea. Then, on the night before the tea could be seized by the customs service, a group of men disguised as Indians boarded the ships and emptied 342 chests of tea into the water. The proceedings were amazingly quiet except for the “ploop, ploop, ploop” of tea dropping into the sea.

A young lawyer from the town of Braintree named John Adams, an obscure cousin of the better- known Boston leader, Samuel Adams, and by no means a lover of mobs, found the event “magnificent.” The “Boston Tea Party,” as it was later called, was “so bold, so daring, so firm, intrepid, and inflexible,” and would have such important and lasting consequences, he said, that “I cannot but consider it as an epoch in history.”

The British government proved him right. It punished Boston with a series of “Coercive Acts” that the colonists promptly renamed the “Intolerable Acts.” Among other things, they closed the port of Boston, throwing hundreds of people out of work, and changed the government of Massachusetts so the Crown had more power, the people less. Then Britain put Massachusetts under military rule, appointing General Thomas Gage as royal governor and sending troops to enforce his authority. From there on, the crisis got worse and worse, without respite.

The First Continental Congress

If Boston and Massachusetts could be punished so severely without a trial or any chance to defend themselves, how could New York or Pennsylvania or South Carolina feel safe?

Twelve colonies, every one but Georgia, sent delegates to a “Continental Congress” in Philadelphia to coordinate their response. The Congress petitioned George III to intercede on the colonists’ behalf, emphasizing the Americans’ loyalty. But the King decided that the colonies were “in a state of rebellion,” and that “blows must decide whether they are to be subject to this country or independent.”

The Battles of Lexington and Concord

![[Picture of Amos Doolittle's painting of the Battle of Lexington]](https://www.learner.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/a-biography-of-america-the-coming-of-independence-c045.jpg)

The blows began on April 19, 1775 after General Gage sent troops to seize colonial arms stored at the town of Concord, some twenty miles outside Boston. On the way they went through Lexington, where local militiamen on the town green began to disperse once they saw how outnumbered they were. Somewhere, someone fired a gun. Then the regulars emptied their muskets into the fleeing militiamen, killing eight and wounding ten.

Amos Doolittle recalled the scene in an engraving he made seven months later. It is much like Revere’s “Boston Massacre.” Again Doolittle showed British soldiers, with their commander urging them on, shooting innocent colonists. Doolittle also recorded the regulars’ march to Concord; an engagement between the provincials and regulars at Concord’s North Bridge and, perhaps most interesting of all, the redcoats’ retreat back to Boston, burning houses along the way, while militiamen from nearby towns shot at them.

The retreat from Concord almost finished off Gage’s army. Once the remaining troops got back to camp in Boston, they pretty much had to stay there. The provincial army that formed across the river in Cambridge saw to that. An ordinary soldier, whose name is unknown, kept a journal of his life in the American army during 1775 and 1776. He had some trouble deciding just what to call the King’s troops. He couldn’t call them, as legend has it, “the British,” since the colonists were still British. He wrote, of “the regulars,” sometimes of “the Gageites.” But after a while he found a better name — “the enemy.”

The Second Continental Congress

![[Picture of George Washington]](https://www.learner.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/a-biography-of-america-the-coming-of-independence-c048.jpg)

Within weeks of Lexington and Concord, a Second Continental Congress met in Philadelphia. It appointed one of its members, an uncommonly tall, dignified Virginian named George Washington, to take charge of the army at Cambridge. Washington had some military experience, none of it especially glorious and some of it disastrous. Even so, he had spent more time as a military officer than most any of his countrymen, and so was appalled at the dirty, disorderly men in the American camp.

Washington quickly began imposing discipline, trying desperately to transform that collection of patriots and adventure-seekers into a respectable army. Meanwhile, the Congress recruited men and officers and gathered military supplies. It took charge of the post office and Indian affairs. It also borrowed money, and eventually issued its own currency. In fact, the Second Continental Congress became the first government of the United States.

It had to assume those powers, it seemed, to prevent the British from crushing the Americans and ending their dream of finding a way to live as free men under the British flag. But reconciliation was becoming increasingly unlikely. The King refused to answer another petition from Congress even though it was written, in a scrupulously respectful way, by our old friend John Dickinson. The colonists’ statements of loyalty, the King told Parliament, were meant “only to amuse” while they schemed to found an independent country. Wasn’t the Congress seizing one power after another?

Thomas Paine’s Common Sense

![[Picture of Thomas Paine]](https://www.learner.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/a-biography-of-america-the-coming-of-independence-c059.jpg)

Then, in the opening weeks of 1776, Common Sense appeared. That pamphlet was the work of Thomas Paine, an Englishman of no particular distinction and little formal education, a man who had been trained as a corset-maker and dismissed from the English customs service before arriving in America less than two years before he wrote Common Sense. With language that spoke to ordinary people, it said what so many native-born colonists were afraid to say. The time had come for America to go her separate way.

The problem wasn’t the ministers, or the Parliament, or even George III as a person, although Paine did call him “the royal brute of Britain”. It was the “so much boasted constitution of England.” The British system of government, Paine argued, had two deadly flaws — monarchy and hereditary rule. Only by governing themselves could Americans secure their freedom and realize the peace that they so deeply desired.

![[Picture of 'Common Sense']](https://www.learner.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/a-biography-of-america-the-coming-of-independence-c060.jpg)

Common Sense spread through the colonies like wildfire, opening among the people a debate over independence that was already well underway among congressmen. And yet, when they looked back over the previous decade, the colonists wondered at the road they had traveled.

How, the freemen of Virginia’s Buckingham County asked in the spring of 1776, had Britain and America become so “incensed” with each other?

The Declaration of Independence

The British saw everything the colonists did to protect their rights as a great outrage. Step by step, mutual confidence and affection had slipped away until they were beyond all hope of recovery. As a result, Buckingham County called for “a total and final separation from Great Britain. Then, perhaps “some foreign power may, for their own interest, lend an assisting hand.”

That became imperative once the colonists learned that George III had hired German soldiers to help put down their “rebellion.” Unless the colonists also got outside support, they would surely be destroyed. It was do or die.

Not everyone agreed. In the end, about a fifth of all colonists remained loyal to Britain. Nonetheless, on July 2nd, 1776, twelve colonies approved a resolution that “these united colonies are, and of right ought to be, free and independent states, that they are dissolved from all allegiance to the British Crown, and that all political connection between them and the State of Great Britain is and ought to be totally dissolved.” A week later New York made the decision unanimous.

After approving independence, Congress spent two days editing a draft declaration submitted by a committee and its draftsman, a thirty-three old Virginian named Thomas Jefferson. Jefferson’s reputation as an eloquent writer preceded his appearance in Congress a year earlier. Now, as the delegates hacked away at his prose, changing words, cutting large passages, rewriting much of the last paragraph, Jefferson suffered visibly. Later he complained bitterly that the delegates had “mutilated” his text.”

On July 4th, the delegates finished their editorial work and ordered the declaration printed and distributed so it could be read “at the head of the Army” and “proclaimed” throughout the land. In that way the people learned that a new nation, the United States of America, had assumed a “separate and equal station” among the “powers of the earth.”

![[Picture of King George's statue being pulled down]](https://www.learner.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/a-biography-of-america-the-coming-of-independence-c072.jpg)

They celebrated independence by shouting “huzzah,” shooting off canons, and watching militia companies parade. Crowds tore down or destroyed symbols of royalty on taverns and public buildings. In New York, people pulled a bronze statue of George III from its pedestal and sent it off to Connecticut, where patriotic women melted the statue down and used the metal to make bullets.

When Americans of 1776 cited the Declaration of Independence, they quoted the last paragraph, the one in which Congress declared that “these united colonies are, and of right ought to be, free and independent states.” Little attention, indeed, so far as I can tell, none at all, was given to the document’s second paragraph, which began: “We hold these truths to be self-evident; that all men are created equal.” Those ideas were expressed in many other contemporary writings. But only the Declaration announced American independence.

And that was the news in 1776.

The American Revolution

To declare independence was one thing; to win it was another. While Congress whittled away at Jefferson’s prose, a massive British fleet arrived at New York. After evacuating Boston, the British had assembled one of the largest sea and land forces ever seen in North America to end this pesky colonial rebellion once and for all. They almost succeeded.

In 1776, the American Army suffered one defeat after another. Washington broke the downward spiral with small but significant victories at Trenton and Princeton, New Jersey, in late December and early January. By then he had convinced Congress that the American cause could not depend on local militiamen, who would serve only for short periods and preferred to remain near their homes. It needed an army of trained soldiers and officers willing to sign up for long terms of service in return for concrete rewards including bounties, respectable pay, and the promise of land at the war’s end.

![[Picture of training poster from the Continental Army]](https://www.learner.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/a-biography-of-america-the-coming-of-independence-c085.jpg)

Thereafter the American cause was primarily defended not by men defending their homes and families, as at Lexington and Concord, but by young, single men, both white and black, with little if any property. Militiamen sometimes supported the Continental Army, as at Saratoga, New York, where they gathered from all over New England to stop an invasion from Canada under the British general “Gentleman Johnny” Burgoyne in October 1777.

The victory at Saratoga gave the signal for France, which was hesitant to join the United States in a losing war, to negotiate an alliance with the Americans. That tipped the odds against Britain. Thereafter, Britain concentrated its attention on the South, where it set off a brutish, bloody civil war. Finally, the British commander, Lord Charles Cornwallis, turned east and settled in at Yorktown, Virginia, on the Chesapeake Bay, waiting for supplies and reinforcements.

![[Picture of Cornwallis' surrender]](https://www.learner.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/a-biography-of-america-the-coming-of-independence-c097.jpg)

Washington and a large body of French troops moved in and mounted a siege while the French fleet prevented the British from rescuing Cornwallis. On October 18, some three years after Saratoga, Cornwallis surrendered. When the British minister learned the news, he exclaimed, “Oh God, it is all over.”

And so another group of negotiators gathered in Paris. The Americans, including the wily Benjamin Franklin and honest John Adams, won extraordinarily favorable terms. The trans-Appalachian west became part of the United States, along with all the land between Canada and the northern border of Florida. And Britain recognized the United States as an independent nation.

Not 1763, but 1776 turned out to mark the great watershed in American history. How would life be different on the other side of that great divide? Now, at least, the Americans could decide that themselves.

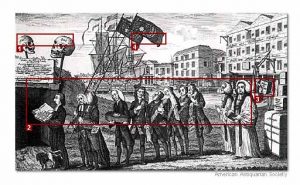

The Stamp Act crisis of 1765 generated a number of political cartoons that expressed opposition to the British government. These, like Revere’s Bloody Massacre, helped shape colonial attitudes toward British actions.

In this cartoon, how does the artist use symbolism and humor to deride Parliament?

Title: The Repeal or the Funeral Procession of Miss Americ-Stamp

Artist: Benjamin Wilson

Date: 1766

Images in support of the colonists circulated on both sides of the Atlantic. Indeed, the market for these broadsides and engravings was probably greater in London than elsewhere, in part because some of the leading artists lived in Great Britain, including Wilson and Philip Dawe (The Bostonians Paying the Excise-man and The Bostonians in Distress), and in part because the tradition of political caricature was well-established in England. Selling for as little as six-pence, these prints were sold in the streets and print-shops and exhibited in taverns and coffee-houses. Benjamin Franklin so enjoyed Wilson’s satire that he sent a copy to his wife in Philadelphia where, shortly thereafter, pirated versions of the engraving appeared. The popularity of these political prints in England attests to support for the colonists by those who sympathized with their grievances and also sought reforms of the Parliamentary system.

Paul Revere’s engraving of The Bloody Massacre was one of many political prints that shaped colonial attitudes toward British actions in America. The Stamp Act crisis of 1765 generated a number of images that expressed opposition to the British government.

1. What are the differences between images and printed pamphlets in terms of the audience they reach and the effect they might have?

2. Can you think of a reference that everyone today would be familiar with but might be lost upon an audience fifty years from now? How do historians recover the meanings of symbols from the past?

Cresswell, Donald. The American Revolution in Drawings and Prints. Washington: [For sale by the Supt. of Docs., U.S. Govt. Print. Off.], 1975.

Jones, Michael Wynn. Cartoon History of the American Revolution. New York: Putnam, 1975.

Morgan, Edmund and Helen. The Stamp Act Crisis; Prologue to Revolution. New York: Collier Books, 1963, c1962.

Richardson, E.P. “Stamp Act Cartoons in the Colonies,” Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography 96,pp. 275-297. July, 1972.

Young, Alfred and Terry Fife. We the People: Voices and Images of the New Nation. Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1993.