Join us for conversations that inspire, recognize, and encourage innovation and best practices in the education profession.

Available on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, Google Podcasts, and more.

Program 9: Slavery/The South and Slave Culture

Donald L. Miller with Pauline Maier and Louis P. Masur

Introduction

Maier: You know, we for so long thought of slavery as a kind of monolithic institution. And we’ve really broken out of that. And we have to– we have somehow in this program to get through the complexity of the institution.

Miller: An insidious institution becomes the foundation of a culture.

Miller: What makes the South– is it land?

Maier: Well, they have a staple product. It’s a plantation economy. It’s a very different form of social organization.

Masur: Part of what we’ve learned about slavery is the notion of the slave family, the notion of a slave culture, and then a wave of studies that have demonstrated beyond any doubt the power of– even within slavery– for African-Americans to create a religion and a culture and a family. But then, did we go too far? I mean, have we forgotten that this is an institution of slavery? An institution of slave labor.

Miller: Today, on A Biography of America, “Slavery”.

Slavery Divides the North and South

![[Picture of Professor Masur]](https://www.learner.org/series/biographyofamerica/prog09/transcript/images/9_masur.jpg)

Masur: In the 1850s, Frederic Law Olmsted, a 28-year-old farmer and landscaper, journeyed from New York through the South. He would become best known for his work at Central Park, but at the time, his reputation rested on his writings. In a series of letters to The New York Times, he described the differences between the two regions. Southern society, he thought, was agricultural, hierarchical, and mainly static. Northern society, by comparison, was industrial, meritocratic, and dynamic. The glaring difference, of course, was free labor vs. slave labor.

Olmsted could not comprehend slavery. In Louisiana he interviewed a slave, and he asked him what would he do if he were free. And the slave responded that he would work, save money, buy a house and land, and he would visit his mother back in Virginia. Slaves, too, had dreams, and in Olmsted’s telling, this particular slave’s dream fit with those of most Americans. Olmsted asked how was it possible that slaveholders could handle simply as property a creature possessing human passions and feelings.

Well, if Northerners critiqued Southern society, Southerners also had plenty to say about Northern society. George Fitzhugh, a self-taught Virginian, published several books during the 1850s. Northern society, he said, was a failure. Wage labor was far more exploitative than slave labor. Free laborers, he claimed, have not a thousandth part of the rights and liberties of Negro slaves. Northern workers, he thought, were slaves without masters, subject to the moral cannibalism of capitalists.

Well these tensions between North and South percolated through the years and they reached one climax as early as 1819 when, Missouri petitioned to enter the Union. If that occurred, the slave states would outnumber the free states 12 to 11. Slavery would inch northward into a region occupied by the free states of Illinois, Indiana and Ohio.

A volatile argument over the admission of Missouri as a slave state ensued. A New York legislator proposed an amendment that would ban slavery altogether, and Southerners in response threatened to dissolve the Union.

A compromise was finally reached when Missouri joined the union as a slave state, Maine entered as a free state, and a line along Missouri’s southern border, the 36° 30″ line, forbade slavery north of the area. Jefferson, in retirement, watched the proceedings, and he commented on this geographic line. He said that “such a line coinciding with a marked principle moral and political, once conceived and held up to the angry passions of men, will never be abolished. And every new irritation,” he predicted, “will mark it deeper and deeper.”

Two Economies

Northerners and Southerners saw themselves as rival, antagonistic, incompatible sections. But in fact, culturally and commercially they shared a great deal. Southerners enjoyed great upward mobility, struggling to get ahead just as Northerners did. They were a migratory people, just as Northerners were, moving west in search of land and opportunity. And the South also engaged in commercial development, committing themselves early on to railroads, turnpikes, even state banks to promote the development of the region.

There were many, many links between North and South, particularly economic ones. Northern merchants were the ones who extended credit to Southern planters. It was Northern ships that got crops to market. And the Southerners, relying on an export economy, basically bought Northern goods and supplied themselves with their needs. For all the talk of Southern backwardness, if we were to consider the South apart from the United States, it would have ranked 4th in the world economy at the time, behind only the Northeast, Great Britain, and Australia.

But the differences, real or perceived, overwhelmed the affinities. The Southern economy lagged behind that of the North. The production of manufactured goods was largely centered in the Northern region. The percentage of the labor force in agriculture was increasing in the South, whereas it was decreasing in the North. And the free states were urbanizing and modernizing far more rapidly than the slave states. The Southern economy may have been growing, but it wasn’t developing.

The Slave South

The greatest difference between the regions, of course, was slavery. But we must take care not to characterize the North as progressive on the issue of race. Even as slavery was coming under attack, some 200,000 free blacks were losing their rights. Tocqueville, always the acute commentator, observed that “the prejudice of race appears to be stronger in the states that have abolished slavery than in those where it still exists. And nowhere is it so intolerant as in those states where servitude has never been known.”

The slave South consisted of 15 states. Of the 11 million inhabitants in the South, 7 million were free, 4 million were enslaved. One third of all Southern whites owned slaves, most of them four to five bondsmen. Less than 1 percent of the white population owned more than 50 slaves. But this number accounted for one fourth of the nation’s slaves.

These planters, while a minority in terms of population, exercised considerable political power and control in society. Over the course of the early nineteenth century, slavery expanded into Alabama, Louisiana, Mississippi, and Texas. Migration was as much a Southern obsession as Northern–moving on to fertile land, reaching out for new territories.

Cotton, in particular, becomes the obsession of the South. It accounted for half of all American exports, and production of cotton accelerated from 700,000 bales in 1830 to over 5 million in 1860. Southerners exported their cotton to England, where the factories would turn it into woven goods and send it out into the world. Southerners truly believed that cotton exercised power in the transatlantic economy. James Henry Hammond of South Carolina declared, “You dare not make war on cotton; no power on earth dares to make war upon it. Cotton is king.”

The monarchical language was suggestive of another aspect of Southern society. The plantation South was a bastion of patriarchal authority and power. It meant that the lives of women were often particularly difficult and challenging, especially in the slave-holding household. One woman proclaimed, “It is the slaves who own me.” Women were expected to be chaste and pure, but men often took liberties with the enslaved.

Mary Chestnut, who kept a diary, wrote, “Ours is a monstrous system. Any lady is ready to tell you who is the father of all the mulatto children in every household but her own. Those, she seems to think, dropped from the clouds.” The reputation of families mattered deeply to Southern men, and honor was a key to Southern identity. Status in the South was public and relational, not private and solitary.

We could talk about the difference between the South as a culture of shame, whereas Northern evangelical culture was increasingly driven by internalized notions of guilt. The defense of honor meant vindication through bloodshed. Andrew Jackson carried a bullet from a duel he had had early in life. And a friend once told Henry Clay that he would have rather have heard of his death than that he’d backed down in a duel.

The myth of the plantation slave-holding South is a persistent one, but non-slaveholders accounted for three-fourths of the population. These were yeomen farmers. Some, especially those in the western parts of the Southern states, opposed the policies of the plantation elite.

But despite their differences, they came to the defense of the social structure. John C. Calhoun offered an explanation as to why. “With us,” he said, “the two great divisions of society are not rich and poor, but white and black. And all the former, the poor as well as the rich, belong to the upper class and are respected and treated as equals.”

The enslaved numbered 4 million souls. More than 75 percent of them worked the land cultivating cotton, tobacco, sugar, and rice. About 15 percent served as domestic servants in households, and 10 percent or so worked in factories and industry. The typical Southern slaveholder may have owned several slaves, but most of the enslaved lived on plantations with twenty or more bondsmen.

Slave Life and Culture

Slaveholders repeatedly praised the institution as paternalistic and proclaimed that the enslaved were contented. But one Southern jurist made clear the rule of law that under-girded the system. “The power of the master,” he said, “must be absolute to render the submission of the slave perfect.”

A photograph taken during the Civil War captures the absolute power of the master, but it also conveys the humanity and agency of the enslaved. The man’s posture suggests pride, defiance, survival. His name was Gordon, and he took advantage of the dislocations of war to run away from a Mississippi plantation into Union lines. An assistant Surgeon General took his photograph and circulated it as evidence of the barbarity and cruelty of the slaveholding class. The image appeared as well in Harper’s Weekly magazine, where it was used as a recruitment poster to enlist black soldiers. In exposing himself, in allowing his picture to be taken, Gordon pushed the cause of emancipation.

In the campaign against slavery, words could be every bit as potent as images. Prior to the Civil War, another runaway slave published a book that introduced readers to the horrors of slavery and explained the nature of slave culture. In his narrative of the life of Frederick Douglass, an American slave, the runaway recounted his journey from enslavement in Maryland to freedom in New England. Douglass exploded the myth of the happy, docile, deferential slave, a stereotype that slaveholders used repeatedly to defend the institution.

He examined, for example, the meaning of slave songs. The singing of the enslaved marked the persistence of oral West African traditions that offered spiritual hope for salvation, not only in the eternal life but in the temporal one as well. Some of the songs contained coded messages. In the lyrics, “O Canaan, sweet Canaan, I am bound for the land of Canaan,” singers were not just bound for heaven but for the North.

Douglass claimed to be utterly astonished to find people in the North speak of the singing among slaves as evidence of their contentment and their happiness. “It is impossible,” he screamed, “to conceive of a greater mistake. Slaves sing most when they are most unhappy.” The songs of the slave, he thought, represent the sorrows of his heart, and he is relieved by them only as an aching heart is relieved by its tears.

Consider another story Douglass told. Colonel Lloyd, a wealthy slave owner, is out riding one day and comes upon a group of slaves working. He asked one of them to whom did he belong? “Colonel Lloyd,” the slave answered. “Does the Colonel treat you well?” “No, Sir,” was the reply. A few weeks later that slave was sold to a Georgia slave trader for having found fault with his master. And to be sold into the Deep South was to be sold to an area where the institution of slavery was in its most violent and least paternalistic form. The story helped explain to a Northern audience why it was that slaves might act as if they were happy and contented.

Douglass’s narrative was eye-opening. It revealed to an unknowing public the nature of slavery. It explained that no matter how docile slaves appeared, no matter how brutal and repressive the institution, the slaves also found ways to resist their enslavement.

Methods of Rebellion

One of the ways in which they resisted was through religion. Slaves held their own prayer meetings and they transformed a slaveholding religion, a religion designed to justify and defend the institution, into one that emphasized deliverance and redemption. Rather than scriptural texts such as, “slaves obey thy masters,” slaves embraced the story of Exodus which told the story of the deliverance of a people from slavery to freedom.

Slaves also resisted by maintaining family, by struggling to preserve marriages and blood relations in the face of terrible uncertainty. The slaves maintained extended kin networks. They preserved taboos against first-cousin marriage, and they stayed connected across different plantations. Douglass recalled that his mother would travel twelve miles at night after a long day in the fields to lie down beside her son.

But in slavery, any family was vulnerable. Husbands and brothers stood by helplessly as wives and sisters were sexually assaulted. Slave owners separated loved ones from one another and sold them to other parts of the South. The internal slave trade relocated hundreds of thousands from slavery in the Upper South to slavery in the Deep South.

The strength of these family ties is indicated by the number of slaves who after the Civil War sought out one another. One freedman who had watched as his wife and children were sold away remarried someone after the Civil War, but then happened to relocate his first wife. He wrote her the following letter. I would come and see you but I know you could not bear it. I want to see and I don’t want to see you. I love you just as well as I did the last day I saw you, and it will not do for you and I to meet. I am married, and if you and I meet, it would make a very dissatisfied family. Send me some of the children’s hair in a separate paper with their names on the paper. My dear, you know the Lord knows both of our hearts. You know it never was our wishes to be separated from each other, and it never was our fault. I think of you and my children every day of my life.”

The letter writer’s literacy was in itself a form of resistance to the institution. Slaveholders tried to keep slaves from learning to read and write. Douglass’s master chastised his wife for teaching the slaves the alphabet, saying it would forever unfit him to be a slave. To be a slave was to be kept ignorant. To be free was to be enlightened. And at night in the slave quarters, some bondsmen struggled to read knowing that where literacy went, freedom followed.

Oral traditions also posed a challenge to the omnipotence of slaveholders. Slaves loved to tell stories, and in those stories they inverted the social order. In animal trickster tales, for example, the world is reversed. The weak outsmart the strong. The powerless become empowered. For example, Brer Rabbit is trapped by a fox and he tells the fox that of all the ways to die, he is most afraid of being thrown into the briar patch. The fox, unable to control its sadistic nature, of course complies, and the rabbit cunningly escapes.

Slaves also resisted by everyday acts, such as stealing food, breaking tools, and feigning illness. As Douglass pointed out, these measures contributed to the racial stereotype of the enslaved as lazy and indolent, but they served as indispensable strategies of everyday survival.

Sometimes, slaves ran away. They took advantage of their knowledge of the land to disappear into the swamps and forests for days, even for weeks. Full communities known as maroons survived for years in isolation. Running away was usually temporary, and runaways paid for their brief escapes with the lash. But the time outside the shadow of the planter’s house provided needed relief from the day-to-day brutalities of the institution.

The enslaved also rebelled both individually and collectively. It was an act of personal rebellion and violence that Douglass placed at the heart of his narrative. He battled his overseer one day, Mr. Covey, and he told his audience that “you have seen how a man was made a slave, now you shall see how a slave was made a man. The bloody fight,” he said, “was the turning point in my career as a slave. It was a glorious resurrection from the tomb of slavery to the heaven of freedom.”

Turner’s Insurrection

Rebellion punctured the myth of the docile, contented slave. In August of 1831 a Virginia slave and self-anointed Baptist preacher named Nat Turner, who had been separated from his wife and had religious visions of bloodshed, rose up in armed rebellion in Southampton County. He was yet another manifestation of the religious impulses of the second Great Awakening. Turner and his followers murdered some sixty slave owners and their families. The state eventually captured and executed the rebels, and folk legend had it that Turner’s body was skinned, his flesh fried into grease, his bones ground into dust.

Following Turner’s insurrection, slave owners became nervous. They imagined widespread conspiracies and they blamed Northern abolitionists for fomenting rebellion in the South. Indeed, both regions imagined dueling conspiracies against one another. Southerners envisioned an abolitionists’ conspiracy to end slavery, whereas Northerners were convinced that a unified slave power was conspiring to spread the institution throughout the land.

But Turner didn’t rebel because of Northern encouragement, and the widespread circulation of his confessions, in which he expressed no remorse whatsoever, did little to ease Southern anxieties. Following the rebellion, “Virginians,” one paper suggested, “could never again feel safe, never again be happy.”

Turner’s insurrection led the Virginia legislature to an unprecedented act. They debated what to do about slavery. “There is a dark and growing evil at our doors. What is to be done?” asked the Richmond Inquirer. Representatives, largely from the western, non-slaveholding part of the state, called for some form of gradual, compensated emancipation that would remove the black presence from the land.

Slavery is Upheld

It was Thomas Jefferson’s grandson, Thomas Jefferson Randolph, who proposed a plan that would have freed slaves born after a certain date and provided for the removal of all blacks from the state. The plan to abolish slavery in Virginia was defeated. In the face of the abolitionists’ critiques from the North and slave rebellion in the South, slaveholders rallied around the renewed defense of their way of life. Dismissing Turner’s rebellion as an aberration, “The slaves,” proclaimed one planter, “are as happy a laboring class as exists on the habitable globe.”

The south unified around slavery. Prior to the 1830s, many Southerners depicted slavery as a necessary evil that would die out on its own accord. But the cotton gin had rejuvenated the institution economically, and attacks on the institution from outside united the region. Fearful of interference on the part of the national government, Southerners urged that liberty, in this case the freedom to own slaves, came before any commitment to Union.

Southern state legislators began to pass laws that forbade the teaching of slaves how to read, limited their movements off of the plantation, and made manumission more difficult. John C. Calhoun described this shift in attitudes. “Many in the South once believed that slavery was a moral and political evil. That folly and delusion are gone,” he proclaimed. “We see it now in its true light, and regard it as the most safe and stable basis for free institutions in the world.”

The Charleston Mercury summarized the lesson learned from decades of conflict: “On the subject of slavery, the North and South are not only two peoples, they are rival, hostile peoples.” Those peoples first met in battle on the frontier in the 1850s. In Kansas, a territory north of the line created by the Missouri Compromise, blood was shed, and warfare over the status of the nation’s soil, slave or free, had begun.

Slavery and Art

The images of the era capture the complexities of slave life. Cartoons that circulated on both sides of the Atlantic illustrated the arguments made by pro-slavery advocates. Slaves are depicted as happy and contented, while free wage earners are portrayed as miserable and impoverished. “What wretched slaves this factory life makes me and my children,” laments one sickly worker.

But daguerreotypes of actual slaves gave lie to the myth of robust, joyful bondsmen. These images, taken in 1850, were meant to support racial theories of a separate creation. And while the fact of their existence demonstrates the power of the master over the bodies of the enslaved, the gaze and posture of these men and women suggests endurance and shared humanity.

Some artists recorded the absolute authority possessed by the master. “An American Slave Market” shows the sale of a runaway slave named George. He’s surrounded by loved ones, but the well-dressed buyers tower over the slaves.

Another painting depicts women and children being inspected and auctioned off as families are broken apart. Those slaves sold at market were often swept South. Lewis Miller, a Pennsylvania craftsman, happened upon a trader marching a group of slaves from Virginia to Tennessee. He wrote down the words of the song that they sang. “Arise, arise and weep no more. Dry up your tears. We shall part no more.”

But part they did, sometimes by running away, sometimes by being sold away, and eventually by dying. John Antrobus, a Southerner who supported the Confederacy, painted this scene of a plantation burial: “In the woods, the slaves could come together and worship in their own way, could share in their travails as a community.” Here the enslaved are at the visual center of the painting, while a white couple, the owners perhaps, stand in the shadows on the periphery, and observe this heartfelt, human scene.

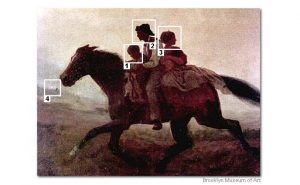

In the end, those who could rode to liberty as a family. Eastman Johnson, a well-known portrait painter, captured such a moment during the Civil War, when a father, mother, child, and baby took advantage of the chaos of battle — the glint of bayonets shine in the distance — and delivered themselves to a new life.

Slaves found a variety of ways to resist their oppression. They told stories, feigned illness, maintained their own religious and cultural traditions, and at times, ran away.

Title: A Ride for Liberty – The Fugitive Slaves Artist: Eastman Johnson Date: Circa 1862

On the back of the canvas Johnson wrote, “a veritable incident in the Civil War, seen by myself at Centreville on the morning of McClelland’s [sic] advance to Manassas.”

Eastman Johnson was born in Maine in 1824, and after some training as a lithographer in Boston, established himself as an itinerant portrait painter based in Portland. As his skills improved, he began receiving commissions for crayon portraits from some of the most distinguished New Englanders including Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, Nathaniel Hawthorne, and Ralph Waldo Emerson.

In 1848, Johnson decided to travel to Germany to study at the famous Dusseldorf Academy where he met with Emanuel Leutze who was at work on his famous painting, Washington Crossing the Delaware. Several years later, Johnson found himself in the Netherlands, at the Hague. He took an interest in common scenes of daily life and in realistic portraits. On his return to America in 1855 he settled in New York and over the next twenty years executed a series of paintings, including Negro Life in the South (1859), Corn Husking (1860), The Pension Claim Agent (1867) and The Cranberry Harvest, Island of Nantucket (1880).

His paintings told stories about common people in America and captured the rhythms of everyday life. His attention to African Americans in particular earned him praise for demonstrating, as one writer put it in 1867, “the affection, the humor, the patience and serenity which redeem from brutality and ferocity the civilized though subjugated African.”

Slaves found a variety of ways to resist their oppression. They told stories, they feigned illness, they maintained their own religious and cultural traditions, and, at times, they ran away.

![]()

1. Johnson painted at least three versions of A Ride for Liberty, all nearly identical. Why might a painter in the nineteenth century execute multiple copies of the same painting?

![]()

2. Because Johnson based his image on an actual incident, A Ride for Liberty might be considered a history painting, a popular genre in which artists used the canvas to narrate historical events. Can the painting be treated as an historical source?

![]()

3. How does a painting differ as an historical source from other documents such as letters and speeches?

Blassingame, John. The Slave Community: Plantation Life in the Antebellum South. New York: Oxford University Press, 1979.

Boime, Albert. The Art of Exclusion: Representing Blacks in the Nineteenth Century. Washington: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1990.

Carbone, Teresa and Patricia Hills. Eastman Johnson: Painting in America. New York: Brooklyn Museum of Art in association with International Publications, 1999.

Levine, Lawrence. Black Culture and Black Consciousness: Afro-American Folk Thought from Slavery to Freedom. New York: Oxford University Press, 1977.

Frederick Law Olmsted

Chronology On The History Of Slavery And Racism 1830 To The End

http://innercity.org/holt/chron_1830_end.html

A chronology on the history of slavery. Includes a paragraph on Olmsted.

Olmsted’s A Journey in the Seaboard States

Frederick Law Olmsted: A Journey in the Seaboard States

http://docsouth.unc.edu/nc/olmsted/menu.html

The text of Frederick Law Olmsted’s A Journey in the Seaboard States. An account of Southern society and slavery.

Frederick Law Olmsted – A Journey in the Seaboard States (1856)

http://odur.let.rug.nl/~usa/D/1851-1875/olmsted/jourxx.htm

The text of Frederick Law Olmsted’s A Journey in the Seaboard States, an account of Southern society and slavery.

George Fitzhugh

Fitzhugh, George “Cannibals All! -or, Slaves without Masters”

http://docsouth.unc.edu/southlit/fitzhughcan/menu.html

The text of Fitzhugh’s Cannibals All! or, Slaves Without Masters, with a title page illustration and biographical information on Fitzhugh.

Jefferson on the Missouri Compromise

Kansas and Kansans – Ch. 12

http://skyways.lib.ks.us/kansas/genweb/archives/1918ks/v1/ch12p1.html

Information on the Missouri Compromise.

USA – An Index on Thomas Jefferson

http://www.let.rug.nl/usa/presidents/thomas-jefferson/

A comprehensive site on presidents. The Jefferson pages include his Inaugural Addresses, State of the Nation Addresses, an autobiography, etc. Link to #260 in his letters for the Missouri Compromise letter.

John Henry Hammond

James Henry Hammond – Cotton is King

http://www.sewanee.edu/faculty/Willis/Civil_War/documents/HammondCotton.html

The text of the Cotton is King speech given before the United States Senate.

Cotton Gin

http://www.richland2.k12.sc.us/rce/cottongi.htm

Information on the cotton gin, with a reference to James Hammond and his quote about cotton.

The War Years

http://xroads.virginia.edu/~CAP/SCARTOONS/carwar.html

A site about South vs. North with political cartoons and a reference to the Hammond speech.

Mary Chesnut

Mary Boykin Miller Chesnut, 1823-1886

http://docsouth.unc.edu/southlit/chesnut/menu.html

The full text of Mary Boykin Chestnut’s “Diary from Dixie,” with commentary and links to additional resources.

Frederick Douglass

Frederick Douglass – The Heroic Slave

http://itech.fgcu.edu/faculty/wohlpart/alra/douglass.htm

A Douglass site with biographical information.

Africans in America – Frederick Douglass

http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/aia/part4/4p1539.html

Provides biographical information on Douglass and a link to his portrait. Includes a reference to The Narrative.

A Short Biography of Frederick Douglass

http://www.frederickdouglass.org/douglass_bio.html

A short biography of Frederick Douglass with links to three of his speeches.

Douglass Narrative

Frederick Douglass: Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, An American Slave

http://www.gutenberg.org/files/23/23-h/23-h.htm

The text of Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, An American Slave, with a biography of Douglass and the preface by William Lloyd Garrison.

Frederick Douglass Portrait

http://www.keele.ac.uk/depts/as/Portraits/douglass.html

A comprehensive Douglass site with images, a biography, links to his writings including The Narrative, and other related links.

The Life of Frederick Douglass

http://www.nps.gov/archive/frdo/fdlife.htm

A Douglass biography, with links to The Narrative, as well as other related links.

USA: Frederick Douglass

http://odur.let.rug.nl/~usa/B/fdouglas/dougxx.htm

The autobiography of Frederick Douglass with an introduction.

PAL: Frederick Douglass (1818-1895)

http://www.csustan.edu/english/reuben/pal/chap3/douglass.html

Provides links to Douglass’s achievements, primary works, selected bibliography, etc.

Freedman’s letter to first wife

A Lost Love in Slavery

http://www.theatlantic.com/personal/archive/2010/06/on-the-sanctity-of-marriage/57760/

The text of the letter to Laura Spicer.

Confessions of Nat Turner

Confessions of Nat Turner

http://odur.let.rug.nl/~usa/D/1826-1850/slavery/confesxx.htm

An introduction to and the text of The Confessions of Nat Turner. Also includes information about the insurrection and court proceedings, and provides a list of people murdered, etc.

Africans in America/Part 3/The Confessions of Nat Turner

http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/aia/part3/3h500.html

The context of and a link to text of The Confessions of Nat Turner, as well as a scanned cover of the document and related links.

Nat Turner 1800? – 1831 – The Confessions of Nat Turner, the Leader of the Late Insurrection in Southhampton, VA.

http://docsouth.unc.edu/neh/turner/menu.html

Provides a link to text of The Confessions of Nat Turner, as well as a scanned cover of the document.

African American Odyssey – Slavery, the Peculiar Institution

http://lcweb2.loc.gov/ammem/aaohtml/aopart1.html

Documents and incidents from the history of slavery, including a description of Nat Turner’s story and confessions with a scanned cover of the original papers.

Calhoun

John C. Calhoun, “Slavery a Positive Good,” 6 February 1837

http://www.douglassarchives.org/calh_a59.htm

The text of Calhoun’s speech, Slavery is a Positive Good.

Today in History, January 13th – The Nullification Crisis

http://lcweb2.loc.gov/ammem/today/jan13.html

Information on Calhoun’s defense of slavery. Provides a link to the original text of Calhoun’s speech against the Compromise of 1850.

Charleston Mercury

Charleston Mercury Extra

http://www.library.wisc.edu/etext/WIReader/Images/WER1273.html

A scanned cover of the Charleston Mercury.