Join us for conversations that inspire, recognize, and encourage innovation and best practices in the education profession.

Available on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, Google Podcasts, and more.

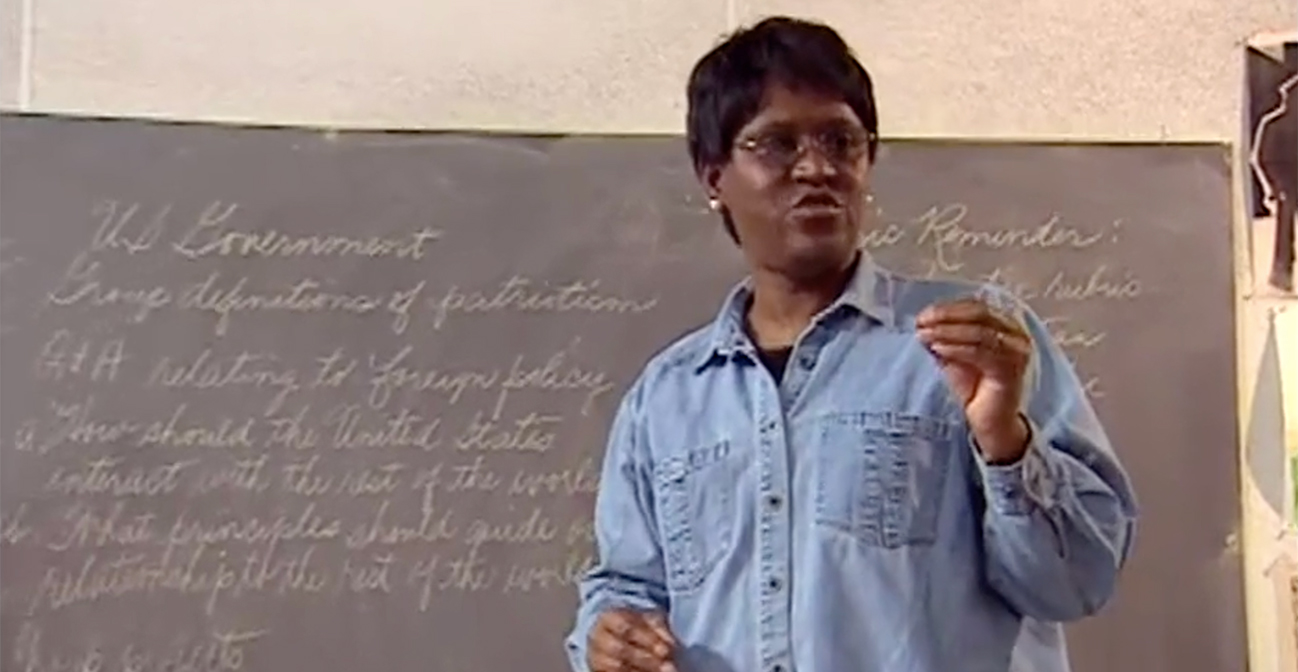

The students whose interview comments are excerpted below were seniors in a one-semester course in U.S. government at Duke Ellington School of the Arts, a magnet high school in Washington, D.C. Here they discuss their experiences creating a Museum of Patriotism and Foreign Policy.

Courtnie: Ms. Chandler starts the day by standing up and asking a warm-up question. If you don’t get to class on time, you will miss that question. I think that’s about 15 points toward your grade, so everyone rushes to class so that we can make that warm-up point.

Leo: One of the big things that Ms. Chandler does is ask questions. She doesn’t ramble on in big long lectures like some teachers do. She gives us the opportunity to “imagine.” She may ask a question that just makes us think. When everyone is agreeing, she’ll play devil’s advocate and turn the theater department on the music department or the museum studies department on the literary media department. It gives us a debate. Not like we’re yelling at each other, but to the point where we’re trying to figure out, “Is this true? Is this how it is? Is this what it’s going to be like?” It opens doors for us.

Myra: Her questions are one thing that really grab attention. The minute somebody asks you a question, you are forced to sit back and think about it. Whether you answer it or not, it’s still in your mind, and I think that is something she uses very powerfully with us. She works at getting us to think. If she does not see our minds working, she knows something is wrong and will come up with some question to get us on the right track of critical thinking. Those questions really, really challenge us. Ms. Chandler finds ways to relate them to us so that we will be able to understand and really make it a personal answer. She tries to let everyone have a chance. If you try to speak more than once, she will say, “Hang on, let somebody else speak,” which I really appreciate because I know if you don’t stop me, I will go on and talk forever. Also, once the question is old, she will move on to a new one. She has a whole list. If we get off track, she asks questions that pull us right back on track. Sometimes I don’t even realize that she is doing it . . . I really enjoyed today because her questions were clear. We started out with a really broad question–What is patriotism?–and then it became more specific, moving into what tactics the U.S. should use in relating to other countries. As you get into it more specifically, it is like you are getting closer and closer to the final realization of the whole discussion, and everybody comes out with their own realization.

David: What I like best about working as a group is there’s always more than one opinion. You’ll always find that someone will disagree with you or have another view and that will make the project better. It will put more color into the project. It will make things interesting because it will give you things to think about.

Leo: Working in a group, you get to share different opinions that you probably wouldn’t get to share with the whole class. [It] helps to exchange ideas among your peers, because those are the people that you’re going to be working with in the future. I think it kind of helps the class along when we get to discuss what we have in common with government and what we don’t have in common with government. People have a lot to bring to the group from different aspects of their art and their background. My friend’s father is a diplomat of Russia, and he just knows so much about their culture and language and government and he brings that to the group, whereas I know about the Dominican Republic and its government and language and I bring that to the group. We compare and contrast ideas and then come to an agreement. Then we bring it back to the class and kind of educate them with what we’ve learned and what we’ve experienced.

Myra: Since we are all seniors [in the theater department], I have spent four years with these guys and it’s just natural to be working with them. We shoot off ideas and see what we all agree with and go back and forth. For the most part we have had similar experiences, or at least explored similar pieces and similar artists, so picking which ones is not simple but it’s a unified experience. As far as what to present and how to make it more interesting to the rest of the class, we have been taught and we know what works for us and what will work for our classmates. I think one incredibly important element is that everyone is involved and everyone contributes the same amount of energy and thinking. The minute that someone loses interest, it all goes downhill and they steal from the rest of the group. They take the focus away. Working with people that I know so well is kind of difficult because we have other things that we want to talk about. But having such specific tasks and knowing exactly what we need to accomplish makes it a lot easier and keeps everybody focused.

Leo: The rubric is the base of the pyramid of what we’re building up to and what we’re building around. [It] is kind of a checklist. It makes us strive for excellence. An A could be: you have to have a five-page paper with an example and a video and an art piece and a song, whereas [for] an F you could just bring in the paper and call it a day. I guess she wants us to do more than a paper. She wants us to go out on our own and experience. She wants you to find things that relate to government. She wants you to go to the newspaper. She wants you to find as many things as you can that relate to [the topic]. That’s how you get an A. I think it’s important for teachers to have an outline of expectations because I think kids tend to stray off the topic and get involved in their own little worlds. I think it pushes them. But to find really good examples that incorporate art [and] your personal life is hard. The rubric she gives us pushes you more than an ordinary English or civics rubric would.

Myra: The rubric is a guideline of exactly what we need to accomplish in our group. That helps because Ms. Chandler gives us different options. We can shoot for an A, a B, or a C and she tells us what we need for each grade. It makes it so much clearer. We can draw out the steps that we need to take to achieve the goals and get every requirement of the rubric met.

David (Theater Group): We decided to pick some pieces or playwrights or directors that reflected American patriotism in other countries and how they’ve defined the American way of life or the American struggles. Like in Clifford Odet’s “Waiting for Lefty,” he defined struggles that a lot of Americans were going through during the 1930s. So I’m going to see how I can show how these citizens in the play–their patriotism–affected their everyday life.

Leo (Theater Group): I’ve known these kids since my freshman year and we know a lot about each other and a lot about our different experiences. So we have a tendency to argue a lot. With this specific topic–patriotism–we really couldn’t agree on one definition. We finally did come to an agreement and they kind of helped me out, as I do them, where they know what I know and I know what they know. If I’m wrong on a topic or they are wrong on a topic, it’s okay, because I’m here to educate you, and you’re here to educate me. It’s kind of an exchange system.

The presentation today was, I think, a mess. I always think I can do better. I liked the fact that we were creating a museum and that we had to incorporate [personal ideas]. I think we should have gotten a little more hands-on and actually brought in more material and more research. We just talked about what we were going to do. I was talking about how I wanted to incorporate the play “Oklahoma.” I think that I should have brought in a poster of the play, a playbill, some songs, some music, or maybe the play itself on video to show a clip. I think I could have done so much more with it. We had a game plan where we were going to bring in our materials, but I think I just got caught up in the weekend–I’m in “Romeo and Juliet” right now–[and] I have a 37-page term paper due. The government project was the smallest thing on my list, because I knew so much about the topic, whereas this 37-page term paper that I have to do, I have to do so much research and it’s extensive. [With] “Oklahoma,” it was something that I didn’t have to research because I knew what I was talking about. Overall I think we did a good job.

The improv, now that was difficult. We initially were going to do a reading of “Waiting for Lefty,” which we did last year. We forgot the scripts, but my friend put us on the spot and asked us to perform. The point that I was trying to make with the improvisation was specifically that authors put a hidden revolution in their scripts. That’s what Clifford Odets was saying, I feel, in his play where this Jewish man was really good at what he did, but he was fired for the simple fact that he was a Jew. It’s kind of sad that people won’t hop on a podium and say stuff like this. It’s kind of sad that artists have to hide it and incorporate it into their work. But as we’ve learned here, theater is a mimic of life. Maybe he wasn’t really trying to hide the fact that this was going on in America. I guess the point that I was trying to get across was that authors, actors, playwrights, singers, dancers put forth this passion that we have for our art, but also combine it with what others have to deal with and the pain of society and the trials and tribulations of what others have to go through. We’re fortunate to be able to get up on a stage and act or dance. Not so long ago, I probably couldn’t have gotten up and did what I did in the classroom. I probably wouldn’t have been allowed to. I think that was one of the big points that I was trying to get across.

Myra (Theater Group): We started with four different nominees for the museum, and we wanted to do a variety of different things. Ms. Chandler gave us some ideas, but they were all movies, so we wanted to first think of things other than movies. We thought of a play by Clifford Odets (“Waiting for Lefty”) that we performed last year. We are thinking of using how that relates to patriotism in particular, and also to see if it has been performed in other countries. Then we wanted to bring in an actor/actress, so we went for Shirley Temple Black. Ms. Chandler also suggested her because she went from [being a] child star [to being a] cultural ambassador that everybody around the world knew and loved. [We wanted] to explore how that transition came about and how she developed such an interest in that area, and then we also wanted to look at Steven Spielberg and the work he has done–what kind of a perception [his movies] give of the country everywhere around the world. Also, the musical “Oklahoma,” and how there is one man who is trying to get it to run in London, and there are just many different feelings on that idea, and whether people would be interested in seeing a very American play in England. I think there are some other places in Europe that are looking at it as well, but we thought that would be interesting as a more current event to bring up.

Selena (Museum Group): Basically, we’re using some different people and events and artifacts to reinforce the ideas of patriotism and foreign policy. We’re also going to try to tie in the other people’s arts and talents so that it can show how patriotism can relate to one’s art. Doing this museum is helping us learn about foreign policy because we have people on our list that we might have not known before. And we have different groups all doing different things that go into foreign policy and patriotism. Each group is bringing something different to the table.

Alex: I find [patriotism] to be a certain love or devotion one has to one’s surroundings or one’s culture. It is something that they can have pride in and just really love.

David: Patriotism can either lead to confusion or it can lead to a lot of qualities [and] successes that can drive a country. Everybody has a different definition of patriotism. I think that’s the biggest lesson I’ve learned. Before I got into civics, I really didn’t care too much about America. I went through U.S. history, but my class was just a class. We were learning from the book. We really didn’t talk about how it affected people. We’re not talking about a country that’s made up of the government. We’re talking about a country that’s made up of people. It gave me an appreciation for all people in America.

Eugenia: I am learning about patriotism. Before this class, I really didn’t know too much about it. I was always anti-patriotism. I didn’t agree with the actions that were being taken by Americans over in Afghanistan but I am learning that it goes a little deeper than that . . . I am getting more understanding, so it’s not just the terms, it’s not just about waving a flag, it’s not just about wearing Army fatigues and joining the service. It’s a little more grounded as to what you believe and what you don’t believe.

When the September [2001 terrorist attacks] thing happened, I was very angry every time I saw a flag. I was very offended at individuals. I didn’t like all of the addresses that were made, and I didn’t like all of the marathons, and I really put myself in a shell when that happened. I lost my aunt in the September 11th ordeal. Every time someone offered condolences, I just didn’t like it. I thought the flag was ultimate disrespect for me and my family. We didn’t fly any flags. I don’t believe that [the flag is] a symbol of freedom. This is the same flag that they flew when we had slavery, when we had terrorists. This is the flag that has flown over many chests and caskets of people who died for something they didn’t believe in. This was not freedom. Equal opportunity has never existed, nor do I think that it will ever exist. It’s not a proud symbol of courage. I think it’s a symbol of cowardice. I think we fly the flag when we are scared, and when we show an outrageous amount of pride, that just turns into arrogance. I don’t believe in killing. I don’t think that we should send bombs and all sorts of things like that into Afghanistan, but this is done, and when I lose family members that help, they give us a flag. It doesn’t help me. It’s not soothing.

[When my aunt died on September 11, 2001] I didn’t participate in any candle vigils. I was just very angry and very anti-American. I didn’t watch the news any more. I did a lot of writing and meditating, but all of the addresses made by the President saying that we are going to declare war and we are going to continue and if you are not for us you are against us, that was just so frustrating to me. So I became very isolated from school, from teachers, from friends, from family. That was my biggest tiff with America, but I guess this class really opened me up to understanding what’s really going on and just being patient.

Leo: [We’ve been talking] about foreign policy and how important it is for us [in the] United States to become cultural ambassadors and represent our country well and not break down into the stereotypes that this country is known for. I feel that we try to get people to kind of convert, like a religion, to our government and our ways of living. It’s affected me because I have a lot of friends who have different national backgrounds and don’t have the opportunity to have what I have because they live overseas. They don’t have freedom of religion. They don’t have freedom of speech. It makes me think a lot about what I have that a lot of people don’t have, and I need to take advantage of that.

The constitution was written back when we were a different type of people. So it’s kind of weird to me that we’ve thrown all this power to Congress now. Back then, people always wanted a greater power to deal with the problems that they had. Now, a lot of people want to be so independent and want to control the government themselves. A lot of people don’t think that the constitution really says anything about the United States anymore.

I think the flag is kind of trendy now. It’s kind of a symbol of patriotism and pride in one’s country, but it’s also been torn to shreds by the fashion market [and] by people in general. I remember my mom telling me that her father fought in the war and she knew all the rules and regulations of how to fold the flag and everything–like you can’t let it touch the ground. The other day I saw some lady dragging the flag on the ground when she was taking it down from her flag post. I don’t think it means as much to us now as it did back then. With September 11th [2001], I think we might have gotten a hint of what it used to mean, but I think it was kind of a new discovery and something that represented a new beginning. Now it’s old and it’s just America. I don’t think that it has the full representation of what it used to be.

Selena: I have a lot of problems with the way people express their patriotism nowadays. After September 11th [2001] everybody just threw up American flags left and right. I can understand if you really feel that way but some people are just doing it to say “I’m patriotic” and they don’t really have any feeling or meaning behind it. My view of patriotism is someone who participates in the democratic process. I feel that we should show patriotism by what we can do for one another. We should show patriotism going out and helping someone or volunteering. You shouldn’t just put up a flag and have that be your only contribution. The people who are fighting this war, they’re the true patriotic people right now. The people who go out of their way to help their fellow man, they’re the true patriots. The other day I was having a discussion with my friend from Turkey and he has a totally different perspective on it. We have so much freedom here. We can say, “I don’t like this country” or burn the American flag. In his country, you can’t do that. You would be sent to prison if you did. He basically told me that people die every day trying to get papers to get into this country and that we should feel appreciative that we’re in this country. I really love this country. I’m thankful that I live here. But that’s not to say that we don’t have a long way to go to be what our forefathers wanted us to be. We need to make it our agenda to be more about global democracy and not try to exploit other countries, not try to exploit other people. Be more about showing human love and kindness instead of just showing patriotism. Patriotism only goes so far in this global world now.

Alex: Ms. Chandler is a great teacher. She really does a lot of work and she has certification for teaching dyslexic children as well so [she] knows how to work with students with [a] variety of learning habits. I learn a lot from her because she caters to my needs. To take it from an artistic standpoint, I learn a lot more effectively.

David: Her teaching style is really incredible because the only things we’ve learned from the books are the amendments and the constitution. She’ll bring in cases. We’ll read from the newspaper and old documents and everything like that that’s incorporated in the chapters in the book. I really like a teacher who doesn’t stick to the book. She’s really liberal in nature and I really like that. It’s amazing to me how she uses government and arts in the same classroom. I never thought anybody could do that. Like how does government relate to the arts. I found as an artist that I have more importance in America. And I found as a U.S. citizen, I feel more accepted and more important. I think the way she teaches is a form of patriotism because she makes you proud of being an American.

Leo: It’s exciting to be in Ms. Chandler’s class because you never really know what’s going to happen. She may plan a lecture on the constitution, but we might get off course and go into something like entertainment law. We do have a genre of studies that she wants us to know by the end of the semester, but we kind of trail off sometimes into different sections of government that still have to do with what we’re talking about. Our questions kind of overwhelm her and she loves that we’re interested. So she’s not going to say we need to keep on track. She’s going to answer them. Being in her class is different than being in other history or government classes because she gets excited as much as we do when we discover something new or when we open a new door. She can relate to us in a lot of ways because she remembers how boring it can get. So she tries to entertain us. She attempts to include our arts in the curriculum.

Myra: Ms. Chandler is a very caring teacher. She is always interested in our performances and in our other classes and in this school. We have 10 classes per semester. When again in my life am I ever going to have to take 10 classes? It just seems like a lot, especially senior year, struggling to get everything done. Ms. Chandler is one of the most understanding teachers when it comes to that. She does a lot of in-class assignments so that we can spend our out-of-school time working on other classes or social life if there is such a thing. And she is willing to compromise. If, for instance, the show choir goes on tour, those students get an extension on projects, and she takes those different aspects into account. Also, she incorporates the art and she takes it seriously and just doesn’t brush it off, as this is just the academics and those are the arts. She ties them in together.

Selena: We always learn in her class by just taking issues that we feel are important, bringing them to the table, and discussing different things. If we don’t understanding something and it’s off the subject, she’ll go out of her way to help us understand. We recently did book reports. My book report had to relate some form of government to our art. The book I chose was “A Taste of Power” by Elaine Brown. She was chairman of the Black Panther Party. I really got interested in learning the Black Panther’s goals for achieving their 10-point platform. Ms. Chandler suggested that I do something on the Black Panther Party for my end-of-the-year project. She’s always making suggestions and giving us things to read. She doesn’t really teach out of the book either. She might use the book as a reference point or something. We have this book that we use sometimes. It’s not like everyday we’re just going into a book, sitting down and writing stuff out of the book and that’s how we learn. We actually learn by her asking us questions, seeing if we know this. If we don’t, we’ll open a newspaper and find out, see what’s going on in the news today. Or we’ll talk about cases and the Supreme Court or something like that. I like the way she teaches because I really don’t learn well from the book. I learn well from actually getting hands-on experience or seeing things that are really happening.

Courtnie: Before, I didn’t really know [much about] dealing with patriotism, government, the world, and all the problems that we face. Because I’m a teenager, that’s something that I really wasn’t focusing on. But when I started going to her class and she started opening my eyes to different situations, I found myself reading the newspaper every day. I found myself watching the news every day. That’s kind of broadening my horizons on the world itself. My mother owns a beauty salon and my father works at the airport. When I started taking Ms. Chandler’s class, it was during the time of [the 2001 terrorist attacks] and my father’s job was shut down and he had to get transferred out to Dulles Airport. He came home talking about so much every day–about the job and the budget and the money. So we were able to actually be on a one-on-one basis, because I was learning it in school and then I was coming home and learning about it on the news and from my dad. I can talk to my parents about a whole lot of stuff now. When I hear them in the house talking about the world and everything, I can have an opinion.

David: I just thought it was going to be loads and loads and loads of information and loads of homework and just sleepless nights of studying the U.S. Constitution and memorizing it. I just have to memorize this useless information that I’m going to forget by my freshman year in college. I just didn’t think it was going to be at all interesting as it is now.

Eugenia: I really didn’t like civics. I didn’t like history. I didn’t like politics because it was always confusing to me. I didn’t like discussion of religion or politics with classmates. I didn’t like debate. I didn’t like to discuss any government outside of America. I didn’t like to discuss American government. Now I understand. We are able to ask questions that you wouldn’t normally ask in the general public, and Ms. Chandler is there to help us answer those questions. When she doesn’t have the answers, she always has another resource for us to go to. In the beginning I didn’t believe that I could be a graphic designer and need civics. [I thought] I could be a literary artist and not have to worry about what was in the past and what was in the present. Now I know the past, so I can give references in my work, which gives your work a more grounded foundation.

Myra: Well, I enjoy government and I enjoy politics and especially foreign affairs and relations between our country and other countries so I was excited about it and I knew Ms. Chandler to [have] a good relationship with the students and an understanding that we have a lot on our plate at the school. So I was really looking at it as a good opportunity to learn more about government and find ways to relate it more to my art.

Leo: I thought studying civics was going to be boring, and that I was going to be asleep in the class. I thought it was going to be back to middle school U.S. government, just memorizing and reciting the constitution and what parts of it were meaningful to us. But since she incorporates so much from our outside lives, like art, [and] shows us how it affects us and how it’s going to affect us in the future, I think it kind of woke me up. This can be a lot of fun. Learning about how the government can work for me and learning about the history of the United States has a great impact on how I’m going to be working tomorrow. I’ve never been so enthralled in government before where I want to vote and I want to participate more because my voice counts, as they say. It’s something that surprised me a lot. I don’t think the class should be called “civics.” I think it should be called “life” because we do so much that incorporates everything that we go through here at an art school, here in the government, here in life.

Selena: It was a requirement. I really didn’t think anything of it. I feel that I need to take a government class because there are things that I need to know to be a part of this country, to be a part of this world so that I can participate. It’s important to have civics education because without it I don’t think people would be aware of what’s going on. I wouldn’t be aware of some of my rights. I know the Bill of Rights. But when you go into depth with it to understand the cases that have been in the Supreme Court and when you know what your human rights are, what you can and can’t do in this country, you learn how to operate in this society.

Alex: To take a course like this was very beneficial to me because I can relate it to my art. I’m a very visual person. I like to do things from a visual and artistic perspective and I think I find much more passion in learning this way than any other conventional way of learning.

David: Before I was an artist, I was a U.S. citizen. As an artist, we represent the United States. Whenever people think of Americans in other countries, what’s the first place they see them? On television or on the stage! So artists are the interpretation of Americans and it’s important for me to know what an American is.

Eugenia: I think artists learn differently. We learn through expression and free expression, and not going strictly from a book allows us to be more artistic, to bring more of ourselves into each assignment. We still have to research. We still have to go on the Internet. We still have to read encyclopedias and go through old books and other resources, so it is still challenging. When I do my presentation, it’s not as if I just do anything that’s called artistic. I still want to perfect it as if she is grading me directly on my art, as well as on the information that I incorporate with it. I think teachers should find what each child’s niche is and work on that, versus just pounding at a weakness in a child and not showing results. If you find out what that child is interested in and learn how to incorporate it within the lesson, I think you have much, much better results.

Leo: [Ms. Chandler] integrates the arts into the curriculum and that kind of spices stuff up a bit, especially when she incorporated artists into government. I thought that government and arts were separate, but she somehow made them come together and that really, really got me excited. I think the best way to get an artist’s attention is to incorporate what they love doing into the curriculum. That keeps them enthralled. It keeps them awake. It gives them an opportunity to ask questions and dive deeper into what we’re talking about. I like the way she incorporates people who are in the department. For example, Paul Robeson was a great artist. I’m a theater major and he relates to me so much. I didn’t know the United States turned its back on him because they looked upon him as a communist. That affected me because he is an artist–that’s all I saw him as. I didn’t know that he was a cultural ambassador. I didn’t know he was known globally for the things that he did overseas. She kind of incorporates art into government, and that makes it a lot easier for me to understand. Then we started discussing how [the arts] affected the government through different types of protests, through art, and education through art. I got really interested when we started talking about books that were banned by the government. That had a literary aspect into it–I love to read because I’m a theater artist–hearing that the government wanted to ban certain books because of the topics that they bring up, like Malcolm X. It offended me. Banning books–that’s just like banning an education.

Myra: To come to this school you have to have a passion for art. Whether you want to or not, you have to spend the extra two or three hours here every day that other high school students don’t. So for her to tie government into what we are passionate about, it just clears up any problems of being interested in the subject or having to suffer through it. While you are learning about government, you are reinforcing what you are learning in the art classes, so it’s a completely rounded education. [Ms. Chandler] will give a presentation on [a] topic and find a way to incorporate your art. She will leave it open so it is sort of up to us to make that connection, which I really enjoy because that is where the real challenge is. She often says, “It doesn’t have to be your particular art, it can be any art.” So if an actor wants to paint a picture, he can do it for her class and get credit for it. It gives the students a chance to explore different artistic aspects of a subject. By using our art, it makes it easier if a student wants to cheat their way out of learning. But then you put so much energy into finding that right way of getting out of learning that you really do just as much work. One of the projects that really challenged me and also became fun was a critique where we could choose a video and a book or two videos or two books that had to do with one topic and do a critique comparing the subject itself and whether they represented it clearly. I chose to do the Watergate scandal, so I watched “All the President’s Men” and then the spoof on “All the President’s Men.” It was really an enjoyable experience. I feel like I learned so much more about that period in history. It became a personal connection, something that now when people talk about it I will say, “Oh yes. I did a report on that back in high school.”

Leo: I think I’d say forget the book and educate yourself. Don’t follow what somebody else wants you to teach because I think the best knowledge is knowledge that is passed on from one generation to another. Like we trust our moms or our dads or our grandmothers with the knowledge that they give us and we keep. It’s kind of like that with Ms. Chandler. We know she’s not reading it out of a book. We know that she knows it. We know that she’s experienced these problems or she has experienced this law or that law. It’s her passion that kind of keeps us on key. I know a lot of teachers who teach English or Spanish or U.S. government [who] don’t even go to community meetings, don’t vote, [and] don’t do the things that they preach to us to do. I think that they need to take what they are teaching us to heart. I think they need to try to be more like a student where they are willing to learn from us as we’re willing to learn from them. You can’t go into a classroom and say, “I have the book. I know all the answers. I’m never going to be wrong” because there are times when you’re going to be wrong. I think the best teachers know that they can be educated by their students.