Join us for conversations that inspire, recognize, and encourage innovation and best practices in the education profession.

Available on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, Google Podcasts, and more.

In this article, Maria Gallo, director of legal studies and a teacher at Harry S. Truman High School in the Bronx, New York, presents three lessons on the First Amendment: The Establishment of Religion, The Free Exercise of Religion, and Putting It All Together: A Round Table Discussion. The lessons include extensive documentation on Supreme Court cases that are relevant to the lessons.

Controversial Issues in Practice

By Maria Gallo

Law-related education is a perfect vehicle for teaching controversial issues.

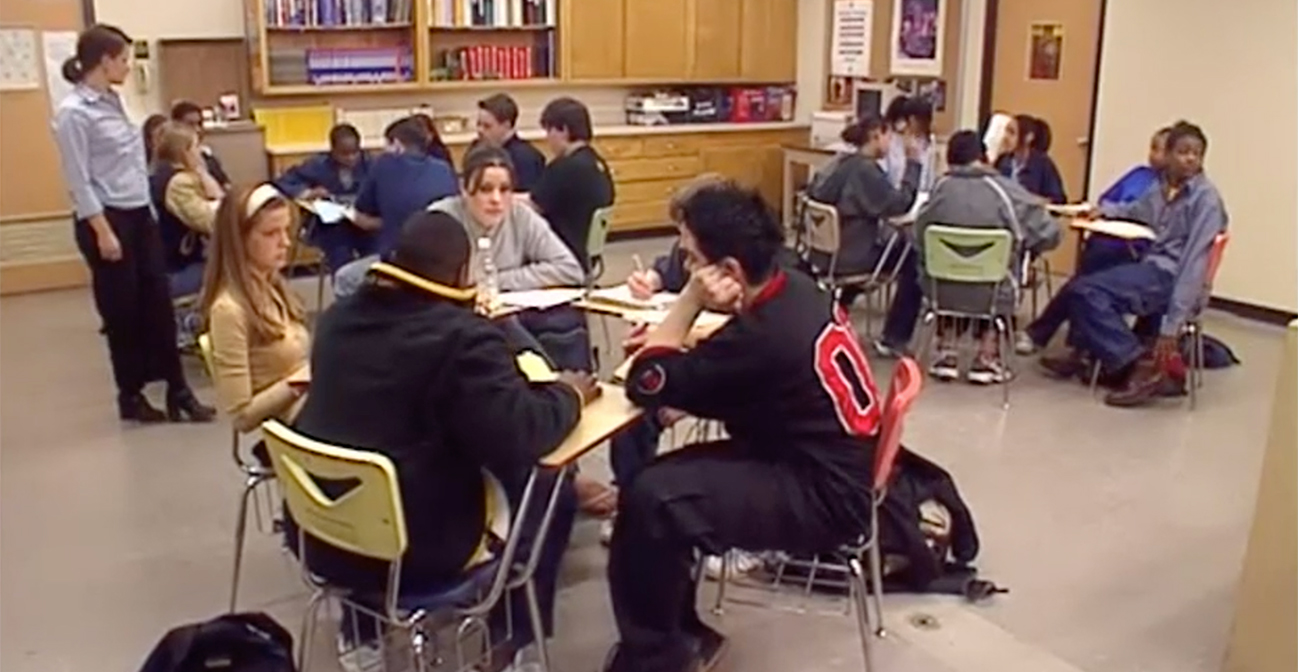

Among my students, I have found that the subject of religion and the state can provoke some very heated classroom discussion, of the kind that spills into the hall and on to the next class when the class ends. The intensity that students bring to the issue offers an excellent opportunity to train them to deal logically and rationally with subjects about which they feel passionately. I require them to learn to listen, seek out the facts, discuss, and debate. A vital goal is accomplished when the issue sparks a proper dialogue–not random rhetoric or generalizations, but talk that is logical, coherent, rational, and factual, even if passionate. And the ultimate success is when the dialogue is not of the teacher’s creation, and the teacher can purposely refrain from the discussion and simply watch.

The lessons outlined below deal with different aspects of church-state relations affected by the First Amendment. The lessons help students at various levels to improve their critical-thinking skills, and to learn more about the Constitution and the role of the judiciary in government. They also show students how, as active citizens, they can shape future trends.

The lessons have been used with a high school senior honors government class as a unit on the Establishment and Free Exercise Clause of the First Amendment. Our school has approximately 3,000 students, 97 percent of whom have minority backgrounds. The students are presently tracked into non-regents, regents, and honors level classes. A large number are immigrants from the Caribbean. I’m happy to say that we have a very diverse population in every way imaginable. The lessons are rooted in an eighth-grade lesson I developed for a law-infused curriculum, which I enhanced and expanded into a unit for my seniors. I have used these lessons with lower-functioning students as well as average students.

There is no magic formula for guaranteeing success for lessons on controversial issues. There are some fundamental prerequisites: knowledge of the unique classroom dynamics created by the intellects and personalities of students; use of materials and tasks to allow for the expansion of student skills and knowledge; a trusting atmosphere which invites inquisitiveness founded on respect for and sensitivity to the right of students to express themselves without ridicule, and encourages students to learn to separate differences of opinion from personal attacks; willingness to change classroom arrangements; and, most important, adaptability and flexibility on the part of the teacher. This adaptability and flexibility needs to be shown in the teaching of these, as well as other lessons. The lessons can be tailored to the needs of particular classes. The time allocated to each must be determined by the teacher vis-à-vis the students’ abilities, curriculum constraints, etc., but each lesson is created to go on for several days.

The lessons require prior knowledge among students of the role of the Supreme Court and its procedures for judging cases, as well as how cases are briefed in Court proceedings. Students should also have had experience with the cooperative learning arrangements used, so that the teacher can focus on providing a structure and set of guidelines to keep students on track, and act as a moderator/observer rather than spend time trying to organize students.

Objectives:

Students are expected to:

Hypothetical Motivator: The lesson starts with the first of the three Hypothetical Cases Involving the First Amendment (see below), a scenario of state funding for textbooks.

Issue Debated: At what point does the relationship between church and state violate the Establishment Clause of the First Amendment?

Materials Used: (1) Texts of the First Amendment* and Fourteenth Amendment, (2) Opinions in Relevant Legal Cases for Lesson One (see below), (3) Hypothetical Cases Involving the First Amendment (see below).

Procedure:

As prior reading, students are required to make themselves familiar with Cochran v. Louisiana. The assignments could vary from texts of related Supreme Court decisions (which my honor students do) to being given excerpts from or teacher-written descriptions of the case (regents or non-regents classes).

The pivotal questions are: how does the decision in Cochran v. Louisiana affect the outcome of our hypothetical case? And how has the court dealt with this issue since Cochran v. Louisiana?

It is now time to set up a jigsaw, which will help students answer the question properly. The following would be the set-up for a class of 35; teachers can adjust it according to class size.

The jigsaw is a wonderful cooperative learning technique. However, it requires a great deal of organization and patience on the part of the teacher. It should be used in simple forms before this unit, to avoid spending a great deal of time trying to keep students organized, which would lead to their becoming frustrated and not participating properly. The various worksheets should be designed to look formal, and their final versions should be posted around the room. This creates an appropriate atmosphere, and helps the teacher keep track of what is occurring.

* First Amendment to the Constitution: Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof; or abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press, or the right of the people peaceably to assemble, and to petition the Government for a redress of grievances. Ratification effective December 15, 1791.

The Issue of Establishment

Cochran v. Louisiana, 281 US 370 (1930). Supreme Court upheld Louisiana act providing funds for textbooks to all students in the state, regardless of the school they attend. Since the books were for secular subjects, the act was seen as benefiting students rather than religion.

Everson v. Board of Education, 330 US 1 (1947). Court upholds free transportation passes to all students.

Release Time

McCollum v. Board of Education, 333 US 203 (1948). Sending teachers into the public schools to teach religion during release time is a form of establishment.

Zorach v. Clauson, 343 US 306 (1952). Court upholds New York State act allowing release time for students to go to religion classes in their own churches.

Prayer in School

Engel v. Vitale, 370 US 421 (1962). Prayer composed by New York Board of Regents is a violation of the Establishment Clause.

Abington School District v. Schempp, 474 US 203 (1963). Pennsylvania law requiring that each school day begin with a reading from the Bible and the Lord’s Prayer is struck down.

Stone v. Graham, 449 US 39 (1980). Posting the Ten Commandments in Kentucky classrooms is held unconstitutional.

Wallace v. Jaffree, 472 US 38 (1985). Alabama statute requiring a moment of silence for meditation and/or voluntary prayer is unconstitutional.

Aid to Parochial Schools

Board of Education v. Allen, 392 US 236 (1968). Court allows for the free loan of books to all children in elementary and secondary schools, since they are for secular education.

Walz v. Tax Commission of New York City, 397 US 664 (1970). Tax-exempt status for religious institutions is upheld.

Lemon v. Kurtzman, 403 US 642 (1971). Establishes a three-prong test to determine if an act violates the Establishment Clause. The test is still used.

Tilton et al. v. Richardson et al, 403 US 672 (1971). The Supreme Court upholds “construction grants” to church-related colleges and universities.

Wolman v. Walter, 433 US 229 (1977). Public payment for field trips by parochial students is banned.

Mueller v. Allen, 103 S.Ct. 3062 (1983). Court upheld Minnesota law that allowed a tax deduction for tuition, textbooks, and/or transportation for any elementary or secondary school.

Holiday Displays

Lynch v. Donnelly, 52 L.W. 4317 (1984). Pawtucket (R.I.) city can include a Nativity scene as part of a seasonal display.

Scarsdale v. McCreary, 105 S.Ct. 1859 (1985). Private crèche scene displayed in the public park in Scarsdale is acceptable.

Allegney v. A.C.L.U., 106 L.Ed. 472 (1989). Two cases in one, with a split decision. (1) A private group’s donation of a crèche, displayed in a courthouse, is a violation of the Establishment Clause, but (2) a Christmas tree, lights, and a menorah in front of the building are not.

The hypothetical situations in Lesson 2 are more personal than those in Lesson 1. The discussions of Lesson 1 will have helped to ease students into debates, so that their opinions are not simply generated by feelings and they can step back and be more objective when they deal with a topic that goes directly to their personal value system and beliefs. Religious beliefs concerning blood transfusions or the acceptance of certain practices are very concrete issues, and students can be expected to voice some very strong opinions.

Objectives:

By the end of the lesson, students should be able to:

Issue Debated:

What right, if any, does the state have to infringe on the Free Exercise of religion as guaranteed by the First Amendment?

Hypothetical Motivator:

Choose one of these two hypothetical situations:

Materials Used:

(1) List of Relevant Legal Cases for Lesson Two (see below); (2) Scavenger Hunt Clues; (3) Hypothetical situations.

Procedure:

Reynolds v. U.S., 1879. Outlaws polygamy.

Pierce v. Society of Sisters, 1925. Struck down Oregon law requiring all students to go to public school, eliminating private schools.

Minerville School District v. Gobitis, 1940. Jehovah’s Witness not excused from saluting the flag in school.

W. Va. Board of Ed. V. Barnette, 1943. Reverses the decision in Gobitis.

Prince v. Massachusetts,1944. Parents must follow Massachusetts labor law if their children help sell religious literature (Jehovah’s Witness case).

Sherbert v. Vernel, 1963. State cannot deny unemployment benefits if employee quits due to a conflict between his/her job and religion.

U.S. v. Seeger, 1965. Allows for test of “religious beliefs” to include beliefs other than those of formal denominations.

Gillette v. U.S., 1971. Gillette was drafted and did not report for duty. Court ruled that he did not qualify for exemption under Selective Service Act, section 27.

Negre v. Larson, 1971. Negre was in the army, but wanted to be released. Court ruled against him as in Gillette.

Tilton v. Richardson, 1971. Court upheld “construction grants” for church-related colleges and universities.

Wisconsin v. Yoder, 1972. Compulsory school attendance forcing Amish children to continue school beyond 8th grade is struck down.

Wooley v. Maynard, 1976. New Hampshire law requiring the state motto to appear on personal cars is struck down.

Widmar v. Vincents, 1981. Students could use university buildings for religious meetings.

Thomas v. Review Board of Indiana Employment Security Division, 1981. State cannot deny unemployment benefits to workers who have a conflict between work and their religious beliefs.

Group 1: Flag saluting as a form of idolatry; Jehovah’s Witnesses and Americanism

Group 2: Public School/Private SchooI Compulsory Attendance

Group 3: Conscientious Objectors v. War Duties

Group 4: Religious Practices v. State Laws; Marriage, Ceremonial participation/practices

Group 5: Labor Laws and Working Conditions

Group 6: Universities and Colleges–Same Limitations?

Group 7: State Laws and Religious Beliefs; Drivers Licenses and State Motto

In a final lesson, students should verbalize and discuss the two broad issues that have emerged from the work done thus far. The suggested framework is a roundtable discussion, with the class divided into two or more groups, each with its own round table. Each member is assigned a particular task: the chairperson, timer, several recorders, and reporters etc.

All members receive a copy of an agenda with two issues for debate:

Assessment:

In evaluating the performance of students, I recommend alternative modes of assessment. Students do get traditional tests in my class, but we are not limited to them. I often grade students on the worksheets completed in groups. Most panel discussions or debates are rated, as are the court decisions which students render. Their reflective pieces during processing can be included in a portfolio. Any of the issues or segments of this unit can be turned into a position paper or term paper for the course.

References

Arbetman, L.P., and McMahon, E. T, and O’Brien, E.L. Street Law: A Course In Practical Law. 2nd Ed. with N.Y. State Supplement. N.Y.: West Publishing Co., 1993.

Gallo, M. and Lesser, D. “Laws–Their Nature and Impact on Society.” Law-Related Education Curriculum, 7-12. Vol 2. New York: G/L Publishing, 1989.

Source: Social Education, Volume 60, Number 1, January 1996. Copyright 1996 National Council for the Social Studies