Join us for conversations that inspire, recognize, and encourage innovation and best practices in the education profession.

Available on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, Google Podcasts, and more.

- The Student Voices Project

- The 26th Amendment and Youth Voting Rights

- Building Consensus

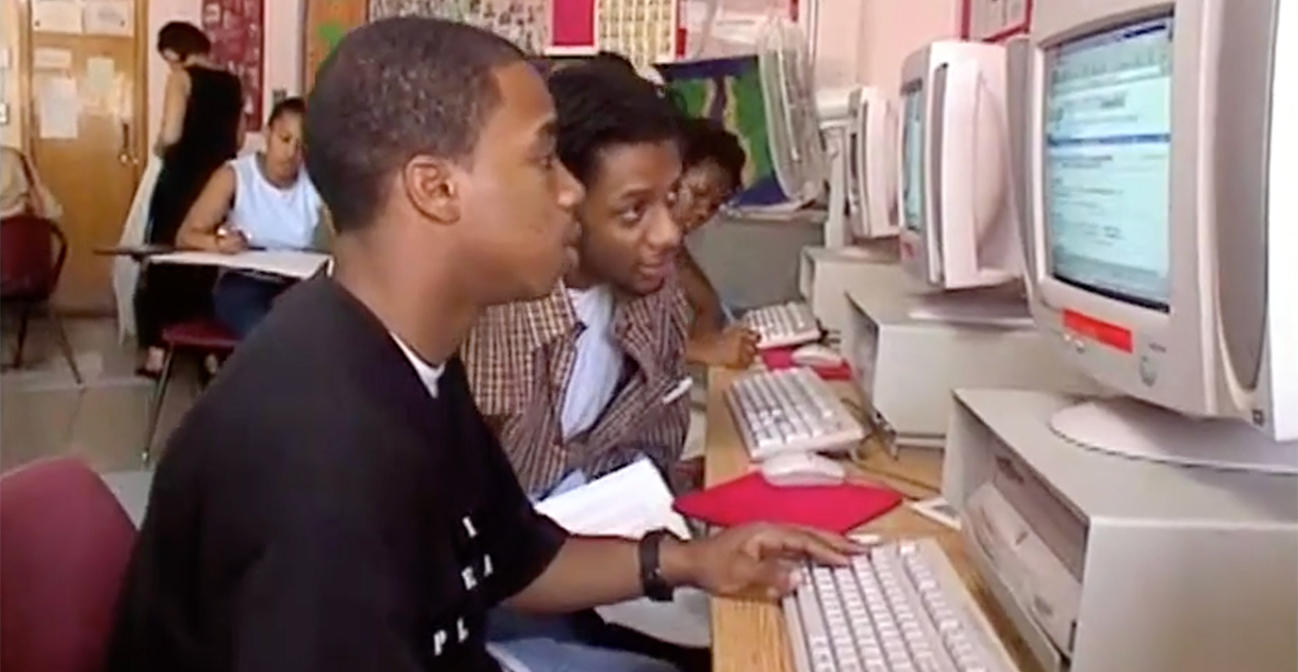

The Student Voices Project encourages the civic engagement of young people by bringing the study of a local political campaign into the classroom. Working with school systems throughout the country, the project helps high school students study the issues and candidates in their city’s mayoral campaign. Each class formulates a Youth Issues Agenda, reflecting the issues that are of most concern to students and their communities. Students use online news sources to follow the campaign and to research where the candidates stand on issues. Through classroom visits and candidate forums, students raise their concerns directly to candidates and hear what can be done about them. Finally, students communicate their concerns to the general public by making their voices heard in the local news media.

The project is an initiative of the Annenberg Public Policy Center of the University of Pennsylvania, with funding from the Annenberg Foundation and The Pew Charitable Trusts. In 2000-2001, the Student Voices Project was implemented in Los Angeles and San Antonio. In 2001-2002, students in Detroit, New York, Newark, Tulsa, and Seattle participated in Student Voices.

Why Student Voices?

Increasingly, young people in America are choosing not to vote in elections. In 1972, when the 26th Amendment to the Constitution extended the right to vote to 18 year olds, 50 percent of Americans aged 18-24 voted in the presidential election. By 1996, however, the percentage of 18-24 year olds who voted in the presidential election fell to only 32 percent. In contrast, 73 percent of people between 65 and 74 reported voting in that election. (U.S. Government, Census Bureau, Report on Voting and Registration in the 1996 Election)

U.S. Census Report on Voting and Registration in November 1996

|

Age group

18-19 20-24 28-29 30-34 35-44 45-54 55-64 65-74 75-84 85 and over |

% of citizens registered

46.7 56.4 61.3 65.5 72.2 76.4 79.8 81.0 79.5 70.1 |

% of citizens who voted

32.4 36.9 44.9 51.1 59.6 66.0 71.4 72.6 67.9 52.2 |

Why Are Young People Not Voting?

A 1999 survey by the National Association of Secretaries of State on American Youth Attitudes on Politics, Citizenship, Government, and Voting examined how young people feel about politics and civic involvement. The study, which noted that young people today are active volunteers, looked closely at why they are not voting when they turn 18. The findings included:

One clear finding of the study was that young people do not feel as if their voices are being heard. Two-thirds of those surveyed agree with the statement, “Our generation has an important voice but no one seems to hear it.”

The Student Voices Project was created to help young people become more informed about public issues and political candidates, to demystify the election process and the mechanics of voting, and to help youth make their voices heard to politicians, the media, and the general public. Between the years 2000 and 2005, the project will work with high school classes in 22 cities, helping students learn about the candidates and issues involved in their city’s campaign for mayor.

What Will Students Do?

Students work as a class to define their own Youth Issues Agenda. They identify concerns in their own schools, communities, and city–and then rank those concerns in importance. Classes study the root causes of problems they see–from neighborhood crime and vandalism to inadequate after-school activities–and investigate alternative ways to approach them. At the same time, students follow news coverage to see whether the mayoral campaigns are addressing youth issues. One of the challenges facing Student Voices classes is to encourage candidates to address issues that are often ignored in campaigns–particularly, issues that matter to young people.

As the campaign proceeds, students have opportunities to question the candidates about their Youth Issues Agenda. They research proposed solutions and discuss alternative solutions with their peers. Students also look at the candidates’ leadership styles and examine what the candidates have accomplished in past positions. Finally, students develop class projects through which they can communicate what they have learned. On Election Day, each class will participate in a mock election for Mayor, and learn more about the actual process of going to the polls and voting.

At the completion of the project, each class will enter its final project in a Student Voices Award Competition, to be judged by members of the community, with cash prizes awarded to the winning schools.

How Do Students Form Youth Issues Agendas and Research Candidates and Issues?

Each Student Voices classroom will have access to a computer with Internet access that connects to the city’s Student Voices Web Site. Here, students will find online campaign news coverage and links to the candidates’ web sites. They will also find background information on the candidates, campaign issues, and how their city government works, including a description of the powers and responsibilities of the mayor. The Student Voices Web Site will also provide opportunities for students to register their opinions on campaign issues, and to engage in online discussions of the campaign with their peers at other schools.

In addition to getting information from the Internet, students will learn firsthand about community concerns in a variety of ways. They may take neighborhood walks around their schools to determine what kinds of problems exist in neighborhoods, from trash not being picked up to vandalism and abandoned cars. In some cases, students may have access to cameras or even video recorders so that they can document community concerns. Students are also encouraged to interview fellow students, teachers, and community and family members to learn more about what others view as important community problems. They may also formulate surveys or polls that assess public opinion about campaign issues, as well as people’s intentions to vote in the upcoming election.

Once students have developed their Youth Issues Agenda, they will have opportunities to question the candidates about those issues. Face-to-face interaction with candidates in classrooms and at forums will be supplemented with online question-and-answer sessions and e-mail requests to campaigns. Students may also have the opportunity to supplement their understanding of issues and public opinion by posing questions to local journalists (including media pollsters), as well as to campaign staffers and media consultants.

How Will Students Make Their Voices Heard?

Throughout the project, students will have opportunities to bring their unique concerns to the direct attention of the mayoral candidates. There will also be many opportunities for students to tell journalists from newspapers and television and radio stations about their Youth Issues Agendas and their viewpoints on the campaign. Each class will develop a final project that helps students communicate what they have learned to the wider community outside their school. These projects may be focused on helping voters understand campaign issues and positions of the candidates, or communicating the importance of voter registration and voting. For example, students may hold issues forums or voting registration drives, documenting the process as part of their final project. They may put together Voters Guides, either in print form or on a Web site, which spell out how each candidate stands on issues of importance to the community. If students have access to the appropriate equipment, they may want to make video or audio documentaries about the campaign, or put together public service announcements for broadcast on radio or television. They may also want to write essays or “op-ed” opinion pieces for local newspapers. At the end of the project, these class projects will be presented at a Student Voices Awards Competition.

Source: http://student-voices.org. Copyright 2001 and 2002 Annenberg Public Policy Center

by Wynell Schamel

One effect of the Vietnam War on the United States was to lower the voting age to 18. Schamel, an education specialist at the Education Branch, National Archives and Records Administration, introduces the 26th Amendment.

The slogan “Old Enough to Fight, Old Enough to Vote” reflected the mood of both the public and its leaders when, in the midst of the Vietnam war, the right to vote was extended to 18 year olds. Codified as the 26th Amendment to the Constitution, the joint resolution was passed by Congress on March 23, 1971, and ratified by the states by July 1–more quickly than any other amendment in U.S. history.

Getting the resolution through Congress took a great deal longer than getting it ratified by the states. Beginning in 1942, Jennings Randolph of West Virginia introduced the resolution in every Congress through the 92nd in 1971. Real momentum toward the extension of the vote began after the negotiation of the peace accords for the Korean War, when President Dwight D. Eisenhower supported Randolph’s proposal to extend the right to vote to those “old enough to fight and die for the United States.” Presidents Lyndon B. Johnson and Richard M. Nixon added similar endorsements. It was not, however, until the pressure created by the antiwar movement of the 1960s intensified that Congress finally passed the Jennings proposal in 1971.

Legal developments during the 92nd Congress caused Congress to seek a constitutional amendment to lower the voting age. In 1970, Congress attempted to lower the voting age to 18 through legislation. That legislation was challenged in court in Oregon v. Mitchell. Because the Constitution gave states the power to establish most voting qualifications, the Supreme Court upheld the statute as it pertained to federal elections but declared the act unconstitutional insofar as it pertained to state elections. Since most of the states required voters to be 21 years of age, this decision would have necessitated separate ballots for federal and state races in the same election. With this complication unresolved, the Presidential election of 1972 would, no doubt, have been not only very expensive but also chaotic. According to Dennis J. Mahony, political science professor at California State University, San Bernardino, “The rapidity with which the Amendment was ratified is attributable to a general desire to avoid such chaos.”

The Amending Process

In Article V of the Constitution, the founders described a process for amending the charter in such a way as to balance two conflicting goals. On the one hand, they wanted to devise a process easier to use than that employed under the Articles of Confederation. At the same time, they wanted to ensure a process that would work only when a strong consensus made it clearly necessary to change the Constitution.

With these opposing goals in mind, the delegates to the Constitutional Convention in 1787 created an amendment process composed of two sets of alternatives. Congress could either propose amendments backed by two-thirds majority of both of its Houses or call a convention to propose amendments at the request of two-thirds of the state legislatures. Afterward, the proposed amendments had to be ratified by either three-fourths of the state legislatures or by conventions in three-fourths of the states. With this process, the Framers attempted to balance the need for adaptability with the desire for stable government.

Since 1789, when the process became the law of the land, more than 5,000 proposals to amend the Constitution have been introduced to Congress, but only 33 have ever received the necessary two-thirds vote of both Houses. Of these, only 27 have been ratified by three-fourths of the states. Change is possible but extremely difficult to enact, thereby meeting both goals of the founders.

Expansion of Voting Rights

At the time the Constitution was written, most eligible voters were white male landowners. Since then, voting rights have slowly expanded as a result of various amendments that abolished restrictions based on race, color, previous servitude, gender, or failure to pay taxes.

The 15th Amendment extended the vote to black males, the 19th removed barriers to the ballot for women, and the 24th abolished poll taxes. Although the 15th Amendment was adopted shortly after the Civil War, real freedom to vote was consistently denied to black Americans for decades through intimidation by violence, cheating at the ballot boxes, and legislated disenfranchisement in the form of poll taxes and literacy tests. Not until the civil rights movement of the 1950s and 1960s galvanized Congress into action to protect the voting rights of all U.S. citizens did black Americans truly enjoy the freedom to vote.

The story of the passage of the 19th Amendment relates a different suffrage struggle. First introduced at the Seneca Falls Women’s Rights Convention in 1848, the amendment opening the ballot box to women was not proposed in Congress until 1870. For almost 50 years, the battle to get the proposal approved by Congress was unsuccessful. With the outbreak of World War I, attention focused on the contributions women made to the war effort in the workplace. Afterward, women successfully argued that if they could work to defend the country, they also deserved the right to vote. Congress was persuaded to approve the amendment in 1919, and it was ratified on August 26, 1920.

The President’s Role

The Constitution makes no provision for the President to take part in the amendment process. But in the case of the 26th Amendment, President Nixon held a ceremonial signing of the certified document on July 5, 1971, inviting three 18-year-olds to add their signatures below his. No doubt Nixon’s decision to publicly endorse the amendment was based on the popularity of the action–indeed, all states had ratified the amendment by July 1–and the recognition that adoption of the amendment enabled approximately 11 million new voters to participate in the national elections of 1972.

Response of Young Citizens

Congressional leaders and others expressed great confidence in American youth during the debate over the 26th Amendment. Senator Randolph described Americans between the ages of 18 and 21 as “educated, motivated, and involved.” Furthermore, he added, “Young people are aware of the world around them and are familiar with the issues before government officials. In many cases they have a clearer view because it has not become clouded through time and involvement. They can be likened to outside consultants called in to take a fresh look at our problems.”

Senator Birch Bayh of Indiana observed, “The surest and most just way to harness the energies and moral conscience of youth is to open the door to full citizenship by lowering the voting age. Youth cannot be expected to work within the system when they are denied that very opportunity.” Senator Bayh also proclaimed, “Passage of this amendment will challenge young Americans to accept even more responsibility and show that they will participate.”

Many political observers at the time predicted that high numbers of young voters would register and vote, thereby having a profound effect on U.S. electoral politics. The fact is, however, that 18- to 20-year-olds have participated at a significantly lower rate than the general population in every election until the Presidential election of 1992.

Source: Social Education, Volume 60, Issue 6, October1996. Copyright 1996 National Council for the Social Studies

The San Diego Unified School District Triton/Patterns Project developed this guide to help both students and teachers understand what consensus means and how to achieve it in group settings.

When working in a group it is important that all members of the group play a role. While the simple majority rules concept works for our nation, in smaller groups it could leave members feeling slighted or out of the loop. Consensus is a strategy that involves everyone playing a role in the decision making of the group. In order for this to be successful, it is important to be open to compromise!

According to the Merriam-Webster dictionary, the definition of consensus is:

Guidelines

Procedure

Source: San Diego Unified School District Triton/Patterns Project, 1999