Join us for conversations that inspire, recognize, and encourage innovation and best practices in the education profession.

Available on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, Google Podcasts, and more.

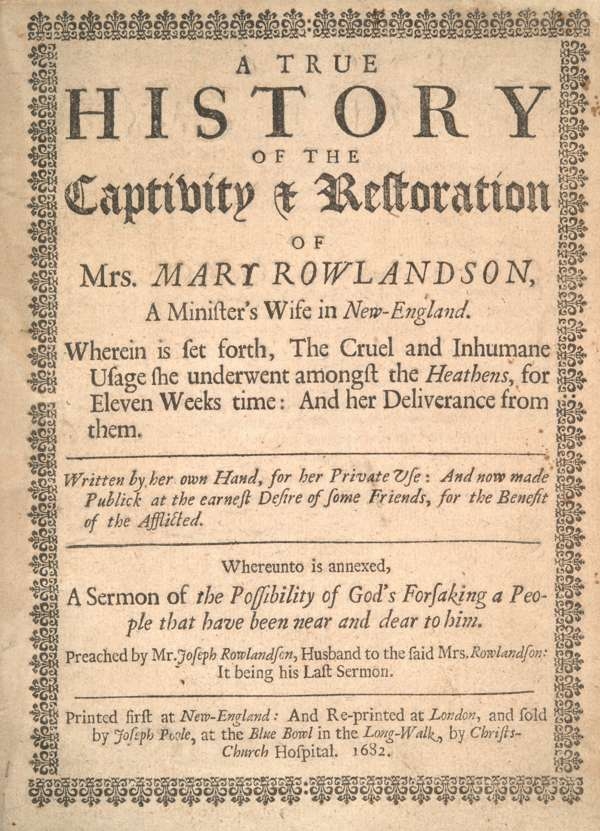

[2788] Mary Rowlandson, A True History of the Captivity and Restoration of Mrs. Mary Rowlandson, A Minister’s Wife in New England (1682), courtesy of Annenberg Rare Book and Manuscript Library, University of Pennsylvania.

ing twenty-four others (including Rowlandson and three of her children) captive. This incident is the basis of Rowlandson’s extraordinary account of her captivity among the Indians, a narrative which was widely read in her own time and which today is often regarded as one of the most significant early texts in the American canon. Rowlandson’s tale shaped the conventions of the captivity narrative, a genre that influenced the development of both autobiographical writings and the novel in America.

The attack on Lancaster and on Rowlandson’s home was part of a series of raids in the conflict that has become known as King Philip’s War, named for the Indian leader Metacom (called “Philip” by the English). Although the war was immediately provoked by the Plymouth colony’s decision to execute three members of the Wampanoag tribe, it should also be understood as the culmination of long-standing tensions between Native Americans and European settlers over land rights and colonial expansion. By the late seventeenth century, many Native Americans in the New England region were suffering the devastating effects of disease and starvation as European settlers encroached upon their homes and hunting grounds.

During her captivity, Rowlandson experienced the same physical hardships the Indians faced: she never had enough to eat and constantly relocated from one camp to another in a series of what she termed “removes.” Her traumatic experience was made all the more harrowing by her Puritan conviction that all Native Americans were agents of Satan, sent to punish and torment her and her community. After eleven weeks and a journey of over 150 miles, Rowlandson was finally ransomed on May 2, 1676, for goods worth twenty pounds. Because Lancaster had been destroyed in the raid, she and her husband spent the following year in Boston, then moved to Wethersfield, Connecticut, where Joseph Rowlandson became the town’s minister. After he died in 1678, Mary Rowlandson married Captain Samuel Talcott and lived in Wethersfield with him until her death in 1711 at the age of seventy-three.

Rowlandson tells her readers that she composed her narrative out of gratitude for her deliverance from captivity and in the hopes of conveying the spiritual meaning of her experience to other members of the Puritan community. In many ways, her narrative conforms to the conventions of the jeremiad, a form usually associated with second-generation Puritan sermons but also relevant to many other kinds of Puritan writing. Drawing from the Old Testament books of Jeremiah and Isaiah, jeremiads work by lamenting the spiritual and moral decline of a community and interpreting recent misfortunes as God’s just punishment for that decline. But at the same time that jeremiads bemoan their communities’ fall from grace, they also read the misfortunes and punishments that result from that fall as paradoxical proofs of God’s love and of the group’s status as his “chosen people.” According to jeremidic logic, God would not bother chastising or testing people he did not view as special or important to his divine plan. Rowlandson is careful to interpret her traumatic experience according to these orthodox spiritual ideals, understanding her captivity as God’s punishment for her (and the entire Puritan community’s) sinfulness and inadequacy and interpreting her deliverance as evidence of God’s mercy.

But in spite of its standardized jeremidic rhetoric, Rowlandson’s narrative is also marked by contradictions and tensions that sometimes seem to subvert accepted Puritan ideals. On occasion, the demands of life in the wilderness led Rowlandson to accommodate herself to Native American culture, which she viewed as “barbaric,” in order to work actively for her own survival even as she cherished an ideal of waiting patiently and passively for God to lead her, and to express anger and resentment even as she preached the submissive acceptance of God’s will. Thus, Rowlandson’s Narrative provides important insight not only into orthodox Puritan ideals and values but also, however unintentionally, into the conflicted nature of her own Puritan identity.

[2115] Harper’s Magazine, The Captivity of Mrs. Rowlandson (1857),

courtesy of the Library of Congress [LC-USZ62-113682].

This is an illustration from an 1857 Harper’s Magazine feature on “The Adventures of the Early Settlers in New England.” This wood-carving print depicts events chronicled in the Narrative of the Captivity and Restoration of Mrs. Mary Rowlandson.

[2788] Mary Rowlandson, A True History of the Captivity and Restoration of Mrs. Mary Rowlandson, A Minister’s Wife in New England (1682),

courtesy of Annenberg Rare Book and Manuscript Library, University of Pennsylvania.

Subtitle: “Written by her own Hand, for her Private Use: And now made Publlick at the earnest Desire of some Friends, for the Benefit of the Afflicted.”

[2916] Charles H. Lincoln, ed., Map of Mrs. Rowlandson’s Removes, Narratives of the Indian Wars (1913),

courtesy of Charles Scribner’s Sons.

This map shows Rowlandson’s “removes” in terms of twentieth-century landmarks.

[4439] Judea Capta Coin (71 c.e.),

courtesy of the American Numismatic Society.

This Roman coin depicts the biblical image of Judea capta (Israel in bondage). Mary Rowlandson’s Narrative typologizes her experience in terms of the Judea capta ideal, understanding her purifying ordeal in the wilderness as a parallel of God’s punishment and ultimate redemption of the “New Israel.”

[7178] Vera Palmer, Interview: “Erdrich and the Captivity Narrative” (2001),

courtesy of Annenberg Media.

Palmer, a distinguished American Indian activist and scholar (Ph.D. Cornell), discusses themes of the captivity narrative as they appear in the poetry of Louise Erdrich.